RESEARCH NEWS

In the workplace, it’s about control

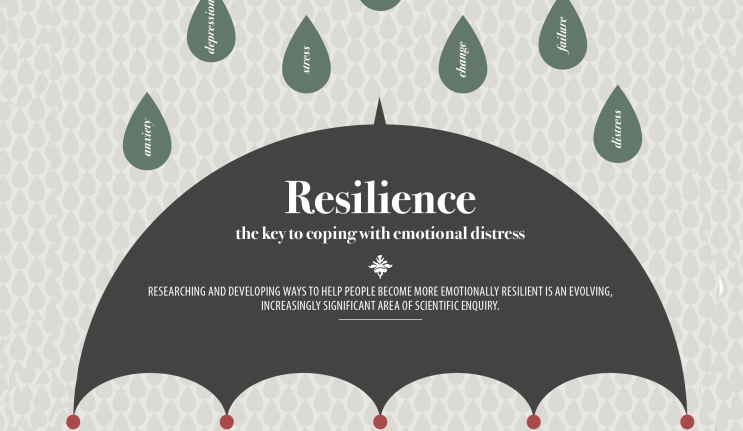

While researching and developing ways to help people become more emotionally resilient is an evolving, increasingly significant area of scientific enquiry, bringing resilience training into the world of work can be problematic, according to Professor Robert Spillane, Professor and past Director of the Macquarie Graduate School of Management.

Trained in psychology and a teacher of philosophy, Spillane is sceptical about the contribution of psychology to management, especially those forms of psychology which deprive individuals of their freedom and personal responsibility. His latest book, The Rise of Psychomanagement in Australia, provides examples of the ways in which managers have used psychology to focus on their colleagues’ weaknesses rather than make their strengths productive, which is the main task of management.

“Traditionally, the role of psychology was to provide the opportunity for individuals to master themselves, not to manipulate others,” writes Spillane. “Resilience training, or stress management as it used to be called, can help individuals increase their self-awareness and offer them new ways of conducting themselves in the face of adversity.”

Research over several decades has shown that a key predictor of occupational stress is how much control people have over their work, Spillane observes. In this respect, bus drivers experience more stress than managers.

The most stressful jobs are those which combine high job demands and low job control. However, decreasing job demands alone is not an effective solution to work stress, since it leads to passivity and boredom. The challenge for managers who want ‘resilient colleagues’ is to maximise their job control by ensuring that their accountability is matched by relevant authority. Professor Spillane is concerned about the growing tendency to link stress, or lack of resilience, to personality traits, and especially personality disorders. This has gone hand in hand with the widespread use of personality tests despite their inability to predict work performance.

Resilience, he argues, is not a personality trait; it’s about the choices individuals make concerning the roles, rules and rewards to which they are subjected. Resilience training at its best, he argues, acknowledges Shakespeare’s view that we are actors in the drama of life and that ‘lack of resilience’ is a communication about a lack of, or loss of, control over some important aspect of one’s life.

Dear Professor Robert Spillane

I really like your comment about Shakespeare and his depiction of resilience. I also agree with you that it is not a personality trait.

I am currently researching a PhD on Resilience to help young children to acknowledge and develop their resiliency skills and find coping strategies so that they will be able to overcome adversity later in life. I would like to cite both your references if possible please? – Are they in any of your published work?

I have already said that Shakespeare uses it as a personality flaw and proceeded to say how Dickens uses young people and the poor to epitomise resiliency and Hardy personifies women as constantly overcoming adversity.

I have one article published to date on coping strategies for young people who self harm:

http://www.abdn.ac.uk/eitn/display.php?article_id=95

Best Wishes

Annette Moir