We’re profiling nominees in the lead up to the 2014 Macquarie University Research Excellence Awards on Thursday 2 October.

This week meet Dr Tom Murray from the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies, who is nominated for an Early Career Researcher of Year – Social Sciences, Business and Humanities Award.

How long have you been a researcher at Macquarie?

Since 2006 when I began a PhD here. I began a full time academic position within Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies (MMCS) in 2012.

I was drawn to research because…

It allows me to follow my fascinations. I have always been curious about the world and ‘research’ is a fantastic way to engage in the pursuit of knowledge in a socially sanctioned way. Many years ago a photographer friend described how working in the media gave him ‘the keys to the city’: the professional role of ‘photographer’ offered him entry to places he never would have been allowed without the organisational imprimatur of reportage and publication. That idea was very important to me, and I realise that in ‘research’ I have the same opportunity. It opens doors to interesting ideas, people and places. I also greatly enjoy the challenge of communicating to an audience – in the hope that my research might stimulate understandings and new ways of being in the world.

What would be an ‘elevator pitch’ of your research area?

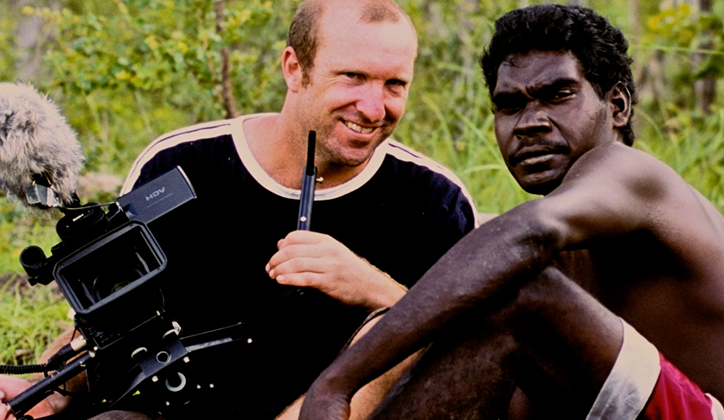

Most of my recent research has been in Indigenous communities and has involved questions of reconciliation, the impact of the federal government ‘intervention’ on remote homelands in Arnhem Land, and the relationship of local indigenous culture to clan estates of ‘land and sea country’. Most recently I have a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award research project investigating the involvement and representation of Indigenous servicemen in WW1. I have also researched experiences of death and dying in contemporary Sydney. My research has always been at the intersection of a range of academic disciplines, but the thing that unites my body of work is investigating the capacity of storytelling across a range of media (text, audio, visual) to communicate ideas that promote empathy and understanding of others.

In layman’s terms, what is the wider impact of your research?

My research has been broadcast and screened to audiences all over the world and has stimulated discussion on Indigenous knowledge systems, on the capacity of acts of contemporary reconciliation to negotiate colonial histories, and on the politics of representation. Two of my films have screened in Australian federal parliament and been part of major discussions on ethics, law, and Indigenous reconciliation (such as a forum at the internationally significant Parliament of the World’s Religions). My most recently completed film Love in Our Own Time has screened at medical conferences, and is on the curriculum of university courses that examine beginning and end-of-life issues within contemporary western society. Many people who have seen this film have said that it helped them greatly in coping with the death of a friend or family member, and helped provide some perspective on their own experience. This is as much of an impact as I could ever hope for.

If I were given $1Million in research funding, the first thing I would do is…

I would collaborate with Warawara, the Department of Indigenous Studies, the Council of Elders, our new Director of Indigenous Strategy, and other colleagues within the University, to initiate a project that developed strategies to promote a stronger dialogue between Indigenous knowledge-holders and the academy. Just to give an example from my own experience in NE Arnhem Land: I work with a number of Yolngu (the people of NE Arnhem Land) intellectuals who are known as ‘Professors’ within the knowledge systems of their own communities. These Professors (and many other Yolngu ‘informants’) provide their knowledge to generations of linguists, geographers, anthropologists, and other academics like myself, who have become scholarly professionals based on the publication of this knowledge. Yet many of the Yolngu intellectuals who have engaged in these research projects continue to subsist on Community Development Employment Program (CDEP – ‘work for the dole’) funds. There are many other similar examples across the country.

This $1m project might investigate how to better acknowledge the contribution of Indigenous collaborators in current research projects being conducted by academic staff and Higher Degree Researchers (HDRs), and perhaps suggest some exemplary practices in the area. Could Indigenous collaborators working with HDRs be granted ‘Supervisory’ roles and stipends to acknowledge their contribution to scholarship? What are the possibilities of more extensive co-authorship, and how might Indigenous contributions be renumerated equitably? How might this serve to attract indigenous students and support their learning needs? What are the costs and benefits to universities in these arrangements?

I would expect that this research could suggest pathways for attracting Indigenous knowledge holders into the tertiary sector as Visiting or Adjunct Professors in ways that are meaningful to the Indigenous Professors themselves, to their communities, and to generations of thinkers – white and black – who would be exposed to a diverse range of ideas and expressions of Indigenous knowledge.

Ultimately, one would hope that engaging a diverse community of Indigenous knowledge holders within tertiary institutions could be transformative to national intellectual life. One could certainly imagine tangible benefits within Indigenous communities, and it is possible to see how such a scheme might encourage and support scholars, and citizens, to navigate and reflect on what differing knowledge systems, and ways of thinking, can bring to solving certain kinds of local and global problems.

In 10 years I see my research…

I see my research continuing to contribute to an ethical engagement, and to understanding, of people in a range of situations and communities. Certainly, I hope to continue my current trajectory of investigating ideas in which I am passionately invested and intrigued, and to communicate them in ways that are useful to both a broad international audience, and to scholars.

My biggest research mentor is/was…

My PhD supervisor Prof Kathryn Millard has been a great mentor, and a thoughtful and generous source of advice and encouragement throughout my academic career. I am also lucky that within MMCCS there is a strong and supportive collegial atmosphere. Additionally, it has been heartening to have a number of colleagues, and in particular the Arts Faculty Associate Dean of Research Professor Catriona Mackenzie, as champions of ‘creative practice’ research within the University. Their initiative and hard work has transformed the research environment in which many of us work.

My favourite and/or most proud research moment was…

My Yolngu colleagues Dhukal and Wuyal Wirrpanda opened our film Dhakiyarr vs the King at Federation Square in Melbourne by declaring that this was ‘the film that they had always wanted to make’.

Learn more about Dr Murray and read about his recent award from the Australian Academy of the Humanities.