From ancient China to modern genetic engineering: a new book on the history of citrus explains how Australian native fruits could save your morning orange juice from disappearing forever .

11 Feb 2025

New book on the world history of citrus reveals that Australian native citrus

could be key to saving the global industry

Australia's native citrus species may hold the key to saving the global citrus industry from collapse, according to a new book by world-renowned botanist and Macquarie Adjunct Professor David Mabberley.

In Citrus: A World History, published in November 2024, Professor Mabberley reveals that Australia has more native citrus species than any other country – a fact previously unknown due to incorrect classification – now revised through his research.

"Australia has at least six native species of the citrus genus whereas China has only five," Professor Mabberley says.

With oranges and other commercial citrus plantations around the world under severe threat from disease, which Australian citrus has so far resisted, “the future of the citrus industry globally may well depend upon our native species", Professor Mabberley says.

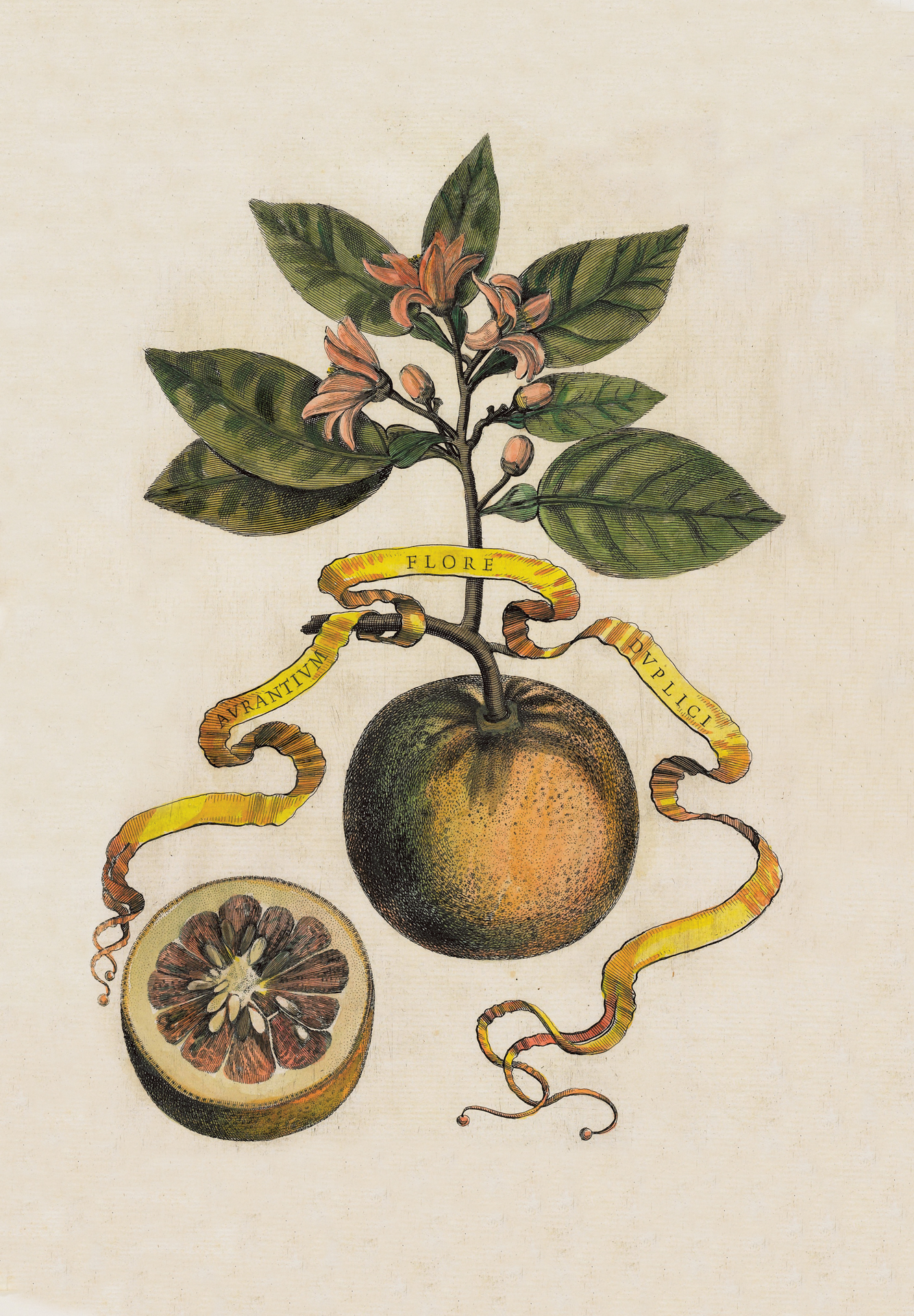

The beautifully illustrated volume includes extensive imagery from classical antiquity to modern advertising, revealing how citrus fruits have flavoured, scented, healed and coloured our world.

Chapters cover the ancient world, herbals and art history, the Dutch Golden Age, empire and vitamin C, and contemporary challenges facing the industry.

Hybrid species

Citrus: A World History represents decades of research, tracing citrus from ancient origins to modern times. Publishers Thames & Hudson, renowned for their illustrated art and culture books, have included beautiful historical imagery and botanical illustrations in the volume.

Professor Mabberley says he structured the narrative in a ‘science sandwich,’ with crucial biological insights bookending the fruits’ rich cultural history stretching from China’s ancient Emperor Yu the Great in the 21st century BC to Macedonian king Alexander the Great around 300 BC, through to the Middle Ages, colonial and modern times.

The book explores everything from the role of citrus in ancient religious ceremonies to the medicinal and insecticidal effects of citrus peel and the influence of citrus on Renaissance art and architecture.

The final chapter, Progress and Perils, examines modern challenges including mass production, cultural impacts and the looming threat of disease linked to the expansion of citrus in monoculture plantations.

"There's no such thing anywhere in the world as a wild orange or a wild lime or a wild lemon," Professor Mabberley says. "These fruits are all complex hybrids. The parental species were originally geographically isolated, but humans took material from one species into the geographical range of another."

Modern oranges, he explains, are a cross between the original wild mandarin of southern China and the pomelo from Indochina. These parent species are now extremely rare in the wild, with the original mandarin surviving only in reduced forests in southern China.

Pages from the book

The illustration above is © The Minneapolis Institute of Art and shows Engravings after Vincenzo Leonardi from Hesperides by Giovanni Battista Ferrari, 1646.. Credit: Thames & Hudson.

Citrus disease

The global citrus industry faces an existential threat from Huanglongbing (HLB), also known as citrus greening disease. The bacterial infection, spread by the Asian citrus psyllid insect, blocks a tree's vascular system. Infected trees can appear healthy until their last functioning vessels are blocked, then rapidly turn yellow and die.

"The Florida industry is about to collapse completely due to this disease," Professor Mabberley says. "The psyllids sit underneath leaves, making aerial spraying ineffective."

The disease spread from its origins in India through Asia, Africa and the Americas. Though Australia remains free of HLB, Professor Mabberley warns its arrival may be inevitable.

"This disease is finishing off the industry in much of the world," he says. “We don't have it yet in Australia, but it's already in New Guinea.”

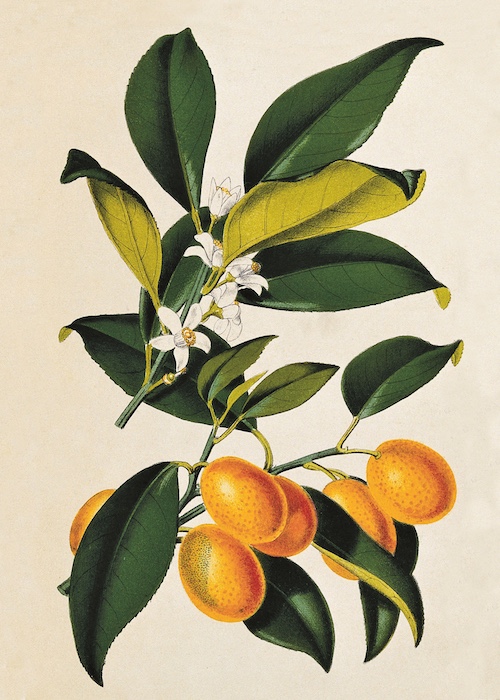

Pages from the book

The illustration above is © The Wellcome Collection, and shows flowering and fruiting stems of the kumquat (Citrus japonica), zincograph, after Walter Hood Fitch, drawn from a plant exhibited at the Horticultural Society in London in 1876. Credit: Thames & Hudson.

Natural resistance

Australia's native citrus species, which range from rainforest trees in Far North Queensland to semi-desert shrubs in South Australia, show natural resistance to the disease.

This includes Citrus australasica, the finger lime, which Professor Mabberley suggests may have evolved its spiky defences against now-extinct megafauna.

"We don't understand why our native species have resistance since they've never been exposed to this disease," Professor Mabberley says.

"The hypothesis is that whatever genetic mechanism confers this resistance was probably selected to combat something else."

Professor Mabberley suggests that genetic engineering may offer the fastest solution for incorporating this resistance into commercial crops. Traditional breeding would take considerably longer, as citrus trees can take up to 15 years to flower from seed.

A team of American researchers will visit Australia in March 2025 to study native citrus species, particularly focusing on their natural disease resistance. The researchers, from the University of California Riverside citrus research centre, will conduct fieldwork in Queensland.

Citrus - A World History by David J Mabberley was published by Thames and Hudson Australia in November 2024. ISBN: 9780500026366

- Fran Molloy

**