Dr Chris Jolly was awarded the Whitley Award this week, after his new book - Field Guide to Northern Territory Reptiles - emerged from a childhood snake obsession.

16 Oct 2024

Ecologist Dr Chris Jolly from the School of Natural Sciences has turned a lifelong obsession into a groundbreaking and award-winning resource, co-authoring the first comprehensive field guide to the reptiles of Australia's Northern Territory.

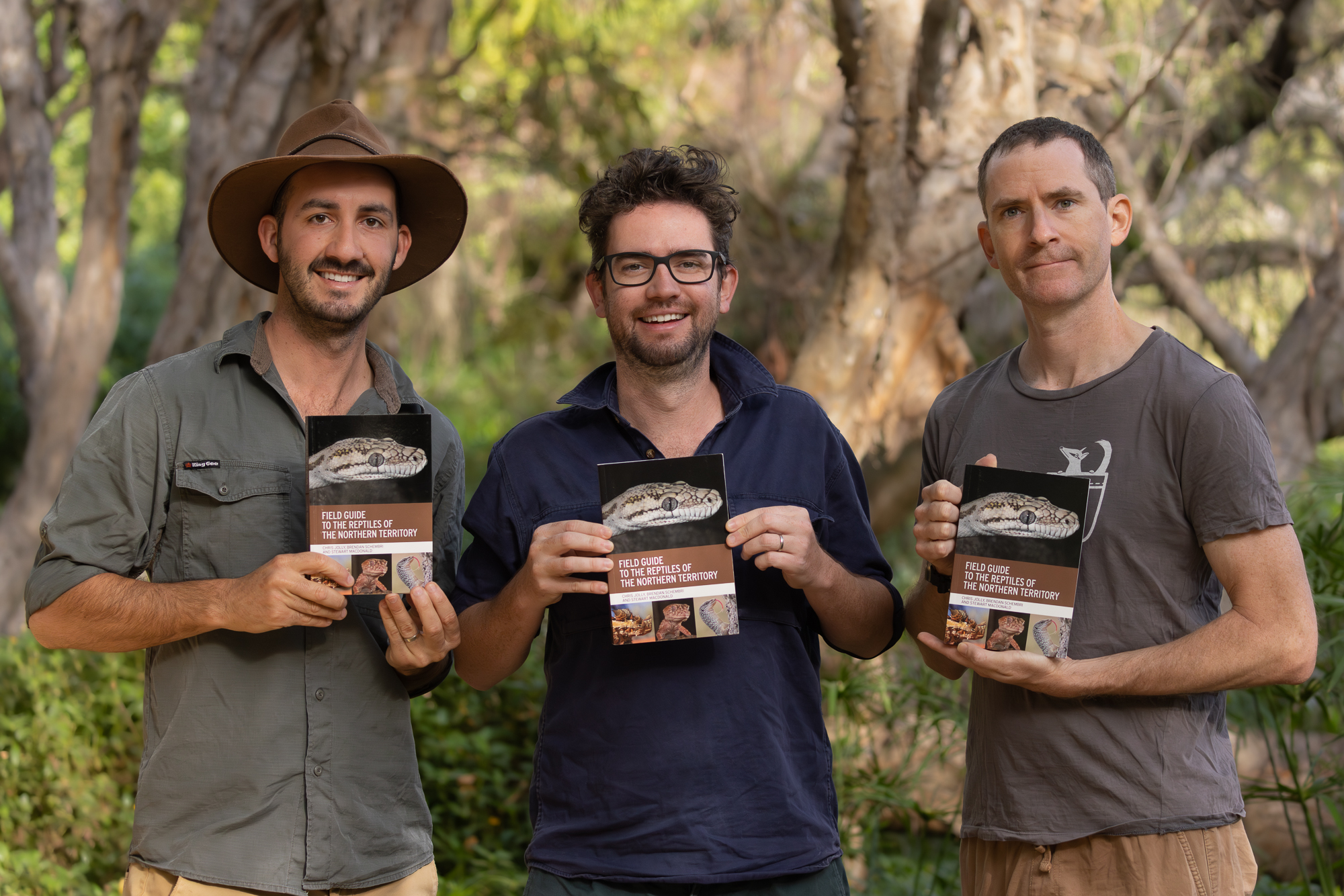

Dr Jolly and his friends and co-authors Brendan Schembri and Dr Stewart Macdonald spent five years creating their “Field Guide to the Reptiles of the Northern Territory,” launched by CSIRO Publishing last year.

This month, their hard work was recognised with the Whitley Award for “Best Field Guide”. The prestigious prize is administered by the Royal Society of New South Wales, one of Australia’s oldest scientific societies, in recognition of the best of Australasian zoological literature.

The Field Guide covers 390 reptile species found in and around the Northern Territory, one of Australia's most biodiverse regions, from crocodiles and turtles to lizards and snakes, with detailed species profiles, distribution maps and identification and natural history notes, along with keys to families, genera and species, to help users identify reptiles in the field.

“We’ve also included species that occur just outside the Northern Territory’s borders, in Queensland, WA or South Australia; reptiles really don’t care about administrative boundaries,” Dr Jolly says.

Early fascination

While his fascination with reptiles began in childhood, growing up in the heart of Sydney meant Dr Jolly’s early exposure to most animals came primarily through books.

“From a very young age, it was clear there was something very wrong with me,” Dr Jolly joked at a recent book launch event.

“It started with dinosaurs, then it was big cats, then it was sharks, before finally resting on reptiles. I was, and against my better judgement, continue to be, completely obsessed with reptiles.”

His adventurous field trips included a memorable journey to the Northern Territory as a teenager to meet up with a fellow reptile-nerd he had met in an online forum.

“At 15, Brendan (co-author Brendan Schembri) and I smashed open our piggybanks to buy plane tickets to the Top End to meet a man we had met on the internet, with plans to find all of the venomous snakes we could without parental supervision,” says Dr Jolly.

Shoebox guide

It was years later, while on a more legitimate reptile-hunting visit to the region, that Dr Jolly realised he desperately needed a field guide – but none existed so far.

“I vividly remember my excitement upon finding a little brown skink on one of my first ecological surveys in Kakadu.

“I had to work out whether I had found the NT endemic skink that shares its name with my wonderful wife Alana - or was it a boring old Menetia maini?”

To his dismay, when asking the field trip leader for some help, he was handed what he describes as “essentially a shoebox full of illicit photocopies of Cogger (Harold Cogger’s Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia), Paul Horner’s Skinks of the NT and various description papers.”

He was astonished that no field guide existed. “The Northern Territory has 20 per cent of the landmass of Australia, but 40 per cent of the Australia’s reptile species occur there.

“We needed a Field Guide to the Reptiles of the NT and if no one else was going to do it, I thought I may as well give it a crack.”

Field guide utility

Field guides are a crucial tool for ecological research and conservation efforts, particularly for biodiversity studies, which rely on accurate species identification.

Dr Jolly’s current research is one such task; he measures the impact of bushfires on biodiversity by counting how many individuals of each species are detected and comparing the changes in particular species abundance through time.

Together with childhood buddy Brendan Schembri and mate Dr Stewart Macdonald, Dr Jolly undertook the mammoth task of creating a new field guide.

“I found my original text message that I sent to Brendan saying, ‘Hey, there's no field guide in the NT. Should we write one? I don’t think it'll be that much work. We’ll get it done in a year.’ It clearly shows how naive we were!”

The team conducted database searches, consulted local experts, and made regular trips to the Northern Territory Museum’s wet store to check unusual records and differentiate between similar species.

Field work was also crucial for the trio, helping fill gaps in their photographic collection and verify various species in different parts of the Territory so their information was as up-to-date and accurate as possible.

Mythical python

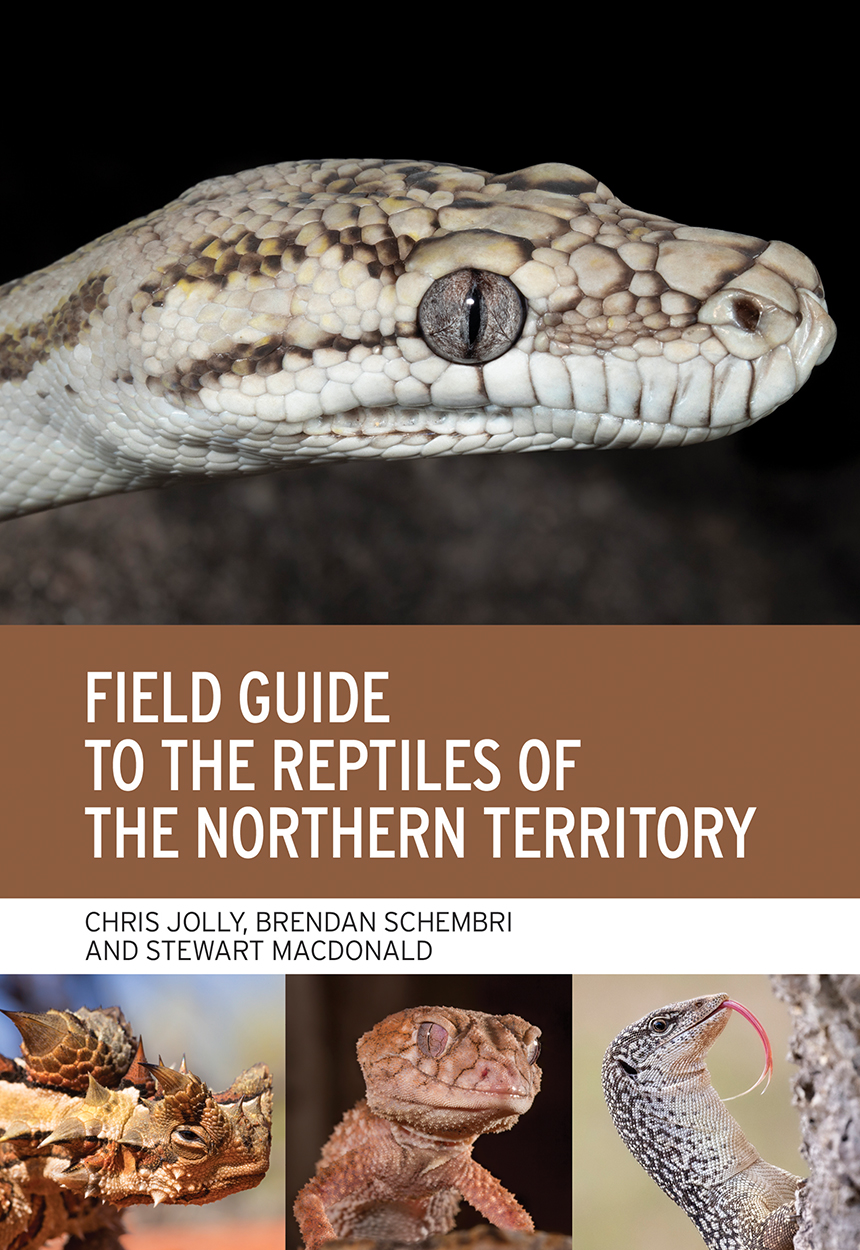

Asked to name a favourite reptile, Dr Jolly points to the cover image. “This is the Oenpelli Python, called Nawaran in every local Indigenous language where it occurs. It’s the pinnacle of reptiles in the Northern Territory.”

The Oenpelli is a massive, near-mythical snake living in the rocky gorges of Kakadu which can reach five metres in length.

“The Oenpelli Python is almost impossible to find. Reptile lovers from all over the world come to Kakadu to look for this snake, and they rarely find one. I’ve been lucky enough to find two in my lifetime so far.”

The guide is already used by Indigenous ranger groups to help identify species during biodiversity surveys, such as in a Kakadu conservation project, where Dr Jolly worked closely with rangers to track down a species thought to be near extinct.

“Western taxonomy is quite different from the different taxonomies used across the many language groups in the Territory, where species can have a number of different names,” says Dr Jolly.

Dr Jolly says that collaborations with rangers show the value of integrating Western scientific approaches with traditional ecological knowledge.

“I thought I was pretty good at spotting reptiles, but I cannot compare with the uncanny ability of Indigenous rangers to spot reptiles, particularly snakes, from remarkable distances. They have a deeper understanding of Country, from thousands of generations of exposure to that environment.”

While the guide has immediate practical application in bridging the gap between scientific knowledge and on-the-ground conservation efforts, reptile classification in an era of easy DNA analysis means that keeping it current will be an ongoing challenge.

“The day that it first went on the shelves, it was out of date, because one species of snakes in our book now had a different name,” says Dr Jolly.

“We will just have to keep going bush in the Territory and finding reptiles to keep the book current!”

Φ