Contemporary architectural responses to climate change are focused on the ultra-efficient use of materials and sustainable designs. But the ancient Elamites, who lived in present-day southwest Iran, worked with their harsh climate, not against it, to create natural cooling systems, and used energy-efficient, renewable, and well-insulated local materials.

Javier Álvarez-Mon, Associate Professor in Near Eastern Archaeology and Art from the Department of Ancient History explains what we can learn from the Elamites when designing buildings in a warming world. He will present a lecture on this topic at the 2019 Iranica Conference on 28 September.

Who were the Elamites?

Javier: “Elam” (ca. 4200-525 BC) is hardly a household name. Amongst the civilizations that participated in the dynamic processes of contact and interchange that gave rise to complex societies in the ancient Near East it has remained the least known and the least understood. Elam – in present-day southwest Iran – spanned not only the agriculturally rich alluvial plain but also parts of the Zagros mountain ranges.

The physical and ecological diversity of this lowland-highland territorial composition determined the material culture, wealth, unique historical resilience, and distinctive personality of Elam, fostering a political, social and cultural character able to adapt and reformulate throughout the centuries.

What do we know about the day-to-day lives of the ancient Elamites and how is this reflected in their buildings?

Javier: The inhabitants of Elam took advantage of their diverse and resource-rich lowland-highland natural environment to develop sophisticated, often politically dimorphic, farming and pastoralist societies. Together with their neighbours in the Mesopotamian “cradle of civilization” these communities spearheaded a revolution in the ways that humans lived and interacted with their environments.

The human genius for adaptability and cooperation took form in settlements and increasingly complex social structures in which we can discern the seeds of today’s global village. Farming and animal husbandry did not put end to hunting and seasonal gathering, but houses and villages transformed the physical environment and redefined notions of individual and communal identities.

Elam was a civilization built on mud-brick, and excavations conducted in the course of over 84 years in the UNESCO world heritage city of Susa, the western Elamite lowland capital, revealed 15 layers of construction dating from 4200 BC to about 1300 AD. The layers dated to the 18th century BC unveiled an irregular urban grid composed of streets, alleys, modest houses and large villas; these are some of the best known examples of ancient vernacular architecture.

What is Vernacular Architecture?

Javier: Sometimes defined as “architecture without architects”, vernacular architecture is the indigenous response to local availability of materials and the environment. The Elamites constructed their houses in regions exposed to intense heat, primarily using mudbrick and palm timber as building materials. This type of architecture seeks to minimize sun exposure, maximize shade, and promote heat loss through natural ventilation. The environment favoured the clustering of buildings, narrow streets and minimal wall openings.

Around ca. 1800 BC Elam’s western capital Susa reached around 85 ha. in extent, undergoing an expansion toward the east with a succession of new constructions in the Ville Royale. These new neighbourhoods have preserved for us unique examples of the adaptation of vernacular domestic mudbrick architecture to the scorching climate of southwest Iran. Photo: Javier Alvarez-Mon.

The core planning principle of these small palaces was determined by a “reception” hall opening to an internal courtyard. These two spaces served together as the focus of household social life and varied in dimensions and number according to household size and social status. The courtyards were paved with baked bricks, perhaps for rain collection, while the publicly shared, unpaved, narrow pathways outside the house were dumping grounds for broken pottery, animal bones, ashes, clay figurines and other discarded objects.

Living quarters avoided the southern exposure and took advantage of prevalent summer winds blowing from the north or northwest. Strategically incorporated internal courtyards offered natural cooling spaces to generate air ventilation, and curved roofs (barrel vaults or domed roofs) and vents increased air circulation and facilitated the exhaustion of hot air. The “reception” hall had thick walls suggestive of a second floor and incorporated sophisticated chimneys with a dual structural design that may have enabled the sweeping of coals to the side and afforded greater control over the cooking or heating temperature.

The formula of a rectangular “reception” hall opening to a courtyard would later become a signature of 1st millennium BC palatial architecture under the Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian rulers; and would remain a defining architectural principle for Islamic architecture, carried over into the New World though the oriental heritage of Spanish-style colonial architecture.

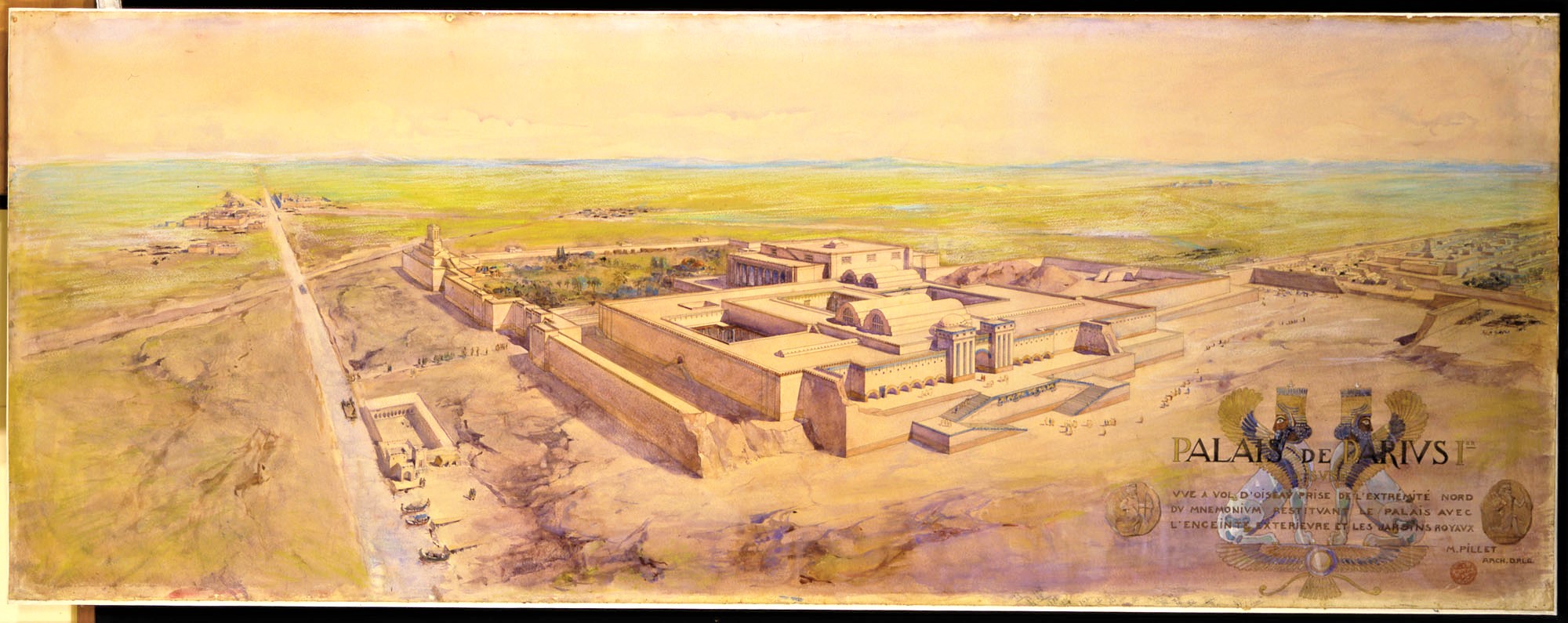

The Palace of Darius at Susa was a masterpiece of mudbrick architecture housing enormous reception halls opening to internal courtyards. Watercolour by Maurice Pillet (1913).

What can we learn from the ancient Elamites when designing buildings for the future?

Javier: As a specialist in the forgotten civilization of Elam, I could not agree more with New York Times columnist Roger Cohen’s description of Iran as “a sophisticated society of deep culture full of unrealized promise”.

Contemporary architectural responses to climate change and the commodifying of nature on an unsustainable scale recognize the necessity of building in “new ways” through the ultra-efficient use of materials and sustainable, passive designs. This requires a significant effort in planning and financing, and in understanding (and reaffirming) the closely knitted relations between architecture, sustainability, culture and identity.

The Elamite vernacular architecture and its pursuit of as-perfect-as-possible adaptations to the natural environment, reveal how working with the environment, not against it, enables practical sustainable responses in house design:

- The minimizing of the building footprint in order to save energy.

- A building layout determined by an optimal location, which considers environmental factors such as seasonality, the direction of the sun, prevalent winds, rainfall and temperature.

- Ideal arrangements of living quarters with the incorporation of internal courtyards and vents for natural cooling.

- The sourcing of local materials offering good insulation and structural reliance.

- Rainwater catchment facilities for storage and irrigation.

These examples of sustainable living dating back almost four millennia offer inspiration and guidance. They compel us to reflect on the degree to which our own consumption culture and a blind notion of what constitutes “progress” have distorted our capacity to recognize ourselves in nature, eradicating our ability to provide sustainable integrated responses to safeguard the future of the planet for the next generations.

From 2020 Macquarie University will offer a renewed curriculum that includes a new Bachelor of Arts with a Major in Egypt and Near East. Macquarie University will be one of just three institutions in the world offering a degree incorporating and specialising in the ancient Iranian civilization of Elam.