Syllable and foot

Topics

Important: You must have installed the phonetic font "Charis SIL" or tested this installation to determine if the phonetic characters installed properly.

The course material for this topic is divided into the sub-topics below.

The syllable: introduction

Felicity Cox, Jonathan Harrington and Robert Mannell

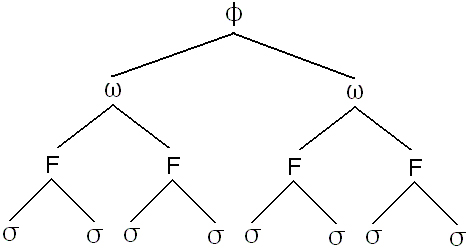

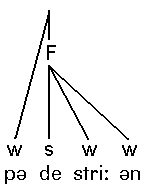

Aspects of phonology above the segmental level comprise units of greater length than the segment. These are referred to as suprasegmental features. Suprasegmental aspects of language encode rhythm and melody and thereby contribute to meaning and give a language its characteristic cadence. Suprasegmental constituent structure is considered hierarchical with the phonological phrase (![]() ) dominating the phonological word (

) dominating the phonological word (![]() ) which in turn dominates the foot (F), the superior constituent to the syllable (

) which in turn dominates the foot (F), the superior constituent to the syllable (![]() ).

).

The syllable is the most basic element in this constituent structure. It has psychological reality as a unit that speakers of a language can identify. Speakers are able to count the number of syllables in a word and can often tell where one syllable ends and the next begins.

Phonetically, it is claimed that when identifying syllables, listeners are responding to sonority. Sonority is the relative loudness of a segments compared with others. Each syllable has a single sonority peak.

What is a syllable? There is no definition of the syllable that phoneticians or phonologists currently agree upon yet the notion of a unit at a higher level than that of the phoneme has existed since ancient times.

The various definitions have a number of commonalities that relate to properties of sound and properties of speakers.

- Sonority or prominence: this is where some sounds are said to have greater prominence than others and these form the basis of syllables. Syllable boundaries fall at points of weak prominence.

- Speaker awareness: this relies on the intuition of the speaker to define syllables. People without any linguistic knowledge are capable of dividing words into syllables. Children can clap syllables before they can read. People who have not been exposed to alphabetic writing systems have greater difficulty segmenting utterances into phonemic units than identifying syllables. Many writing systems are syllabic where each symbol represents a syllable. Japanese is an example

The CV (consonant followed by vowel) structure has been suggested as a basic phonological unit.

What’s the evidence that a CV sequence is a phonological unit?

- Almost all languages have CVCV or CV words.

- If a language has CCV words, it also has CV words.

- Hardly any language has V or VC words without CV ones. One of the rare exception to this is the Arrandic group of Aboriginal languages

- The first systematic utterances of children are usually of this form regardless of language type.

The syllable is seen as a unit of neural programming rather than primarily muscular or acoustic events. If an error is made in the duration of a phoneme, the error is compensated for within the syllabic unit suggesting that articulatory events are programmed in terms of higher-level articulatory units rather than single phonemes.

Other evidence for neural programming comes from speech errors such as slips of the tongue. When spoonerisms occur, for instance, and one consonant is substituted for another, this only occurs in same syllable position. eg initial consonants are swapped for initial consonants and final consonants for final consonants. eg beas and peans, or else whole syllables are switched "drugtator dic Baron". Errors do not involve random switching between segments.

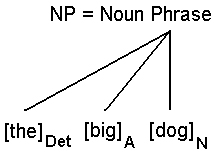

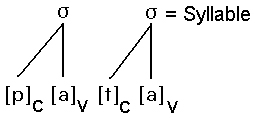

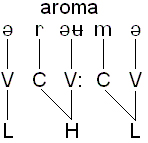

The syllable is a structural unit and within that structure we can identify a sequence of consonants (C) and vowels (V). Just as in grammar we can parse a grammatical structure, in phonology we can parse syllabic structure.

| Grammatical category is signaled not just by paradigmatically different classes but also by their sequential arrangement from which we parse a superordinate NP structure (in this example). | So too in phonology: we parse a hierarchical syllable structure from a sequential arrangement of C's and V's | |

|  | |

| [biɡ]A means: 'big' belongs to the grammatical category Adjective | [p]C means: /p/ belongs to the phonological category Consonant. |

Syllables:

i. Most syllables have a single vowel plus zero or more consonants (occasional syllables have a syllabic consonant rather than a vowel).

ii. No syllable has more than one vowel. Vowel-like sequences in a single syllable are interpreted as diphthongs or semi-vowel plus vowel sequences.

iii. Depending upon language-specific rules, syllables have certain numbers of consonants before and after the vowel.

Open and closed syllables

Closed syllables are syllables that have at least one consonant following the vowel. The most common closed syllable is the CVC syllable.

Open syllables are syllables that end in a vowel. The most common open syllable is the CV syllable.

English monosyllabic words

English has a large number of monosyllabic words. All monosyllabic words in English have a single vowel. By examining the legal consonant+vowel sequences in English monosyllabic words we can get a good idea of what types of syllable structure are legal in English.

a) Open syllables

| V | "I" | /ɑe/ |

| CV | "me" | /miː/ |

| CCV | "spy" | /spɑe/ |

| CCCV | "spray" | /spɹæɪ/ |

b) Closed syllables

| VC | "am" | /æm/ |

| VCC | "ant" | /ænt/ |

| VCCC | "ants" | /ænts/ |

| CVC | "man" | /mæn/ |

| CVCC | "bond" | /bɔnd/ |

| CVCCC | "bands" | /bændz/ |

| CVCCCC | "sixths" | /sɪksθs/ |

| CCVC | "brag" | /bɹæɡ/ |

| CCVCC | "brags" | /bɹæɡz/ |

| CCVCCC | "plants" | /plænts/ |

| CCCVC | "spring" | /spɹɪŋ/ |

| CCCVCC | "springs" | /spɹɪŋz/ |

| CCCVCCC | "splints" | /splɪnts/ |

It is clear from this list that English has a very flexible syllable structure. There are languages at the opposite extreme that have only CV syllables.

It should be noted, however, that there are nevertheless considerable constraints on which phoneme sequences are permissible in English syllables. Such constraints are called phonotactic constraints and these constraints are very language-specific. Nevertheless, there is a universal tendency for phonotactic constraints to conform mostly to sonority profile constraints.

Phonotactic constraints and sonority are dealt with below.

Syllable structure

Jonathan Harrington and Robert Mannell

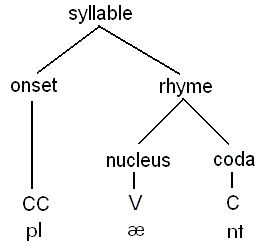

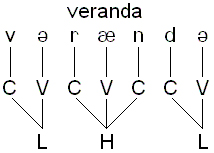

The syllable can be structured hierarchically into the following components:-

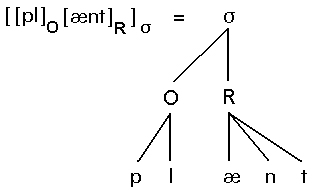

In this example, the English word "plant" consists of a single CCVCC syllable. This syllable has been broken up into its onset (any consonants preceding the vowel) and its rhyme (all phonemes from the vowel to the end of the syllable).

The rhyme has been further divided into the nucleus, which in the vast majority of syllables is a vowel (the exceptions are syllabic consonants) and the coda, which are any consonants following the nucleus.

Some other examples:

| flounce: |

onset = /fl/ rhyme = /æɔns/ nucleus = /æɔ/ coda = /ns/ |

| free: |

onset /fɹ/ rhyme = /iː/ nucleus = /iː/ coda zero |

| each: |

onset zero rhyme = /iːt͡ʃ/ nucleus = /iː/ coda = /t͡ʃ/ |

The rhyme

The rhyme is the vowel plus any following consonants.

'plant'. Syllable is composed of an Onset = /pl/ and a Rhyme = /ænt/

(the rhyme is obligatory = the head of the syllable)

There is phonological evidence of at least two kinds to suggest that the vowel forms a unit (the rhyme) with the following consonants

- restrictions on phoneme combinations

- sound change

Evidence for the rhyme: phoneme combinations

There are often restrictions within syllable units (within the Onset; within the Rhyme); but not many restrictions on phoneme combinations between syllable units (between the onset and the rhyme)

For example:

there are few restrictions on what vowel can follow /fl/ (column 1) but many restrictions on the type of vowel that can precede /lf/ (column 2)

| /fl/+ vowel/ | /vowel + /lf/ | |

| iː | fleece | * |

| ɪ | flip | sylph |

| ʉː | flew | * |

| e | fled | self |

| æɪ | flake | * |

| əʉ | flown | * |

| ɔ | flop | golf |

| ɐ | flood | gulf |

| oː | floor | * |

| æ | flack | Ralph |

| æɔ | flounce | * |

| ɑe | fly | * |

* means -- no word with this combination

Evidence for the rhyme: sound change

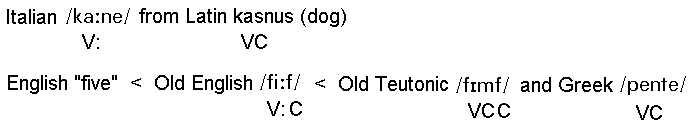

A vowel and consonant in the rhyme are often merged historically resulting in a long vowel (known as compensatory lengthening).

This kind of merger hardly ever happens in a CV onset-rhyme.

The syllable and phonotactic constraints

Jonathan Harrington and Felicity Cox

Phonotactic constraints

We have seen in the preceding section that all languages build their words from a finite set of phonemic units. It is also true that in all languages there are constraints on the way in which these phonemes can be arranged to form syllables. These constraints are sometimes known as phonotactic or phoneme sequence constraints and they severely limit the number of syllables that would be theoretically possible if phonemes could be combined in an unconstrained way. Some simple examples of phonotactic constraints in English include: all three-consonant clusters at the beginning of a word start with /s/ ('sprint', 'squire', 'stew' etc); nasal consonants cannot occur as the second consonant in word-initial consonant clusters unless the first consonant is /s/ (e.g. there are no words in English than begin with /bm dn/ etc), although this is certainly possible in other languages (e.g. German which allows /kn/ in words like 'Knoten', meaning 'knot' - we can see from the spelling that English used to allow this sequence as well). Another important point about phonotactic constraints is that they vary from language to language, as this example of English and German has just shown.

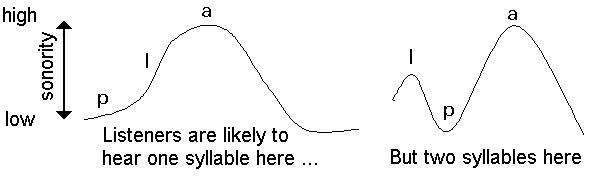

We will consider firstly why languages have phonotactic constraints. The main reason is to do with the limits on the talker's ability to pronounce sequences of sounds as one syllable, and the listener's perception of how many syllables he or she hears from a given sequence of phonemes. Consider for example a sequence like /pʁ/ i.e. a voiceless bilabial followed by a voiced uvular fricative. Most of us with some training can produce this sequence (e.g. /pʁa pʁit/ etc.) as a monosyllabic word even though it doesn't occur in English. Now try reversing the order of the cluster. With some phonetics training, you could almost certainly produce /ʁp/, but what is much harder (even for a trained phonetician) is to produce the sequence before a vowel such that the resulting sequence is monosyllabic. For example, try /ʁpi/ -- even your best attempts at producing the /ʁ/ followed by the /p/ will probably still lead to a percept of two syllables when /ʁp/ precedes a vowel.

One of the main reasons, then, why languages have phonotactic constraints is because their sequential arrangement is itself a cue to the number of syllables in a word. When we produce an English word like 'print' for example, we want to convey to the listener not only that this word is composed of a certain number and type of phonemes, but also that the word happens to be monosyllabic: and the listeners' perception of how many syllables there are in a word depends to a certain extent on the arrangement of phonemes in sequence, as we saw from the example of /pʁ/ and /ʁp/ that has just been given.

In order to explain why listeners hear e.g. /pʁi/ as one syllable, but /ʁpi/ as two, we need to appeal to what has been called the syllable's sonority profile.

Sonority profile

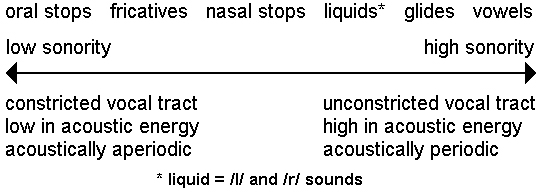

Sonority is an acoustic-perceptual term that depends on the ratio of energy in the low to the high part of the spectrum, but it is also closely linked with the extent to which the vocal tract is constricted. In general terms, open vowels like [a] have the highest sonority because the vocal tract is open and a large amount of acoustic energy radiates from the vocal tract. At the other extreme, voiceless oral stops have least sonority because there is no acoustic energy during the closure in which the vocal tract is constricted.

Languages prefer to build syllables with the most vowel-like sounds nearer the middle, and the least vowel like sounds (=oral stops, voiceless fricatives) near the edge(s). Syllable structured in this way are said to conform to the sonority profile.

i.e. oral stops are less sonorous than fricatives which are less sonorous than nasals etc.

If they conform to the sonority profile, consonants sequences in syllable onsets increase in sonority from left to right and consonant sequences in syllable codas decrease in sonority from left to right. From this we can predict which consonant sequences are more probable for syllable onsets and codas.

| probable /pla fni lju sma pfle/ /alp ims oɹt/ | less probable /lpa nfi jlu lfpe/ /apl ism otɹ/ | Why? The syllables on the right have two sonority peaks -- and so it's much more difficult to produce them so that they sound like one syllable…for example: |

So a language is more likely to build monosyllabic words from the combination of phonemes on the left than on the right.

Languages prefer to build syllables from phonemes such that the sonority rises from the left syllable edge, then reaches a peak (at the vowel), and then falls. Therefore, a language is more likely to have a syllable like /pla/ than /lpa/, because in /pla/ the sonority rises from its lowest value for /p/, increasing for /l/, and reaching a peak with /a/. Similarly, a language is more likely to have /amp/ than /apm/. We can now see why listeners might hear two syllables in /ʁpa/ even if a talker intends only one: because the sonority is higher for /ʁ/ (since it is a fricative), then falls for /p/, then rises again for /a/ (and the condition to hear one syllable would be that there is a progressive rise in sonority from the syllable's left edge).

It must be recognised that there is only a tendency for syllables to conform to the sonority profile. So while most syllables do conform to the sonority profile in English, many syllables that contain a consonantal cluster with /s/ do not. An example of a syllable that does conform to the sonority profile is 'flounce', phonemically /flæɔns/ in (Australian) English. In the initial consonant cluster, /f/ is less sonorous than /l/ which is less sonorous than the diphthong; in the final consonant cluster, the diphthong is more sonorous than /n/ which is more sonorous than /s/ and so the sonority rises from the left edge of the syllable, reaches a peak at the diphthong, and then falls over the final cluster. But a word like 'spin' violates the sonority profile (because /s/ is more sonorous than /p/) and so does 'act' (because /k/ and /t/ are equally sonorous). The sonority profile is therefore a general tendency which determines many, but by no means, all phonotactic constraints.

Phonotactic constraints: syllable onset, coda and rhyme

When discussing phonotactic constraints, it is helpful to structure the syllable hierarchically in terms of an onset and a rhyme, and sometimes also the syllable coda. See the section on "Syllable Structure" above for more details.

We can then discuss phonotactic constraints:

- within the onset

- within the coda

- within the rhyme

The most extreme phonotactic constraints (extreme in terms of the greatest restrictions in the sequential arrangement of phonemes) are in the onset. For example, in English: /f/ can only be followed by approximants (as in 'fly'), there are no consonant phonemes that can follow affricates etc.

The phonotactic restrictions in the coda in English are often (but not always) a mirror-image of those in the onset (as you'd expect if the syllable's legal phoneme sequences are strongly influenced by the sonority profile). For example, English allows /pl/ in the onset ('play') and /lp/ in the coda ('help'); it allows /fɹ/ in the onset ('free') and, for rhotic dialects (e.g. Gen. American English), /ɹf/ in the coda ('surf'). But there are also many permissible coda sequences that are allowed whose mirror-image is disallowed in the onset (e.g. /mp/ as in 'lamp', but no /pm/ in the onset).

Finally, there are far fewer restrictions in the rhyme -- these are to do with the restrictions on nucleus-coda combinations. But as an example of a rhyme constraint, there are no long vowel + /ŋ/ sequences (no words like 'seeng', 'flowng', although the onomatopoeic 'boing!' is allowed).

Language-specific constraints

Languages differ in the kinds of onsets they allow:

/kn/ | /skw/ | /sb/ | /vr/ | |

| English | no | yes | no | no |

| German | yes | no | no | no |

| French | no | no | no | yes |

| Italian | no | no | yes | no |

In English the maximum number of consonants that can make up the syllabic onset at the beginning of an isolated word is three. The first can only be /s/, the second has to be /p, t, k/, and the third has to be an approximant /w, j, ɹ, l/.

| eg. | splayed | strayed | scrape |

| spew | stewed | skewed | |

| squish | squawk | squeal |

These are all CCCVC

When the third consonant is /w/ then the first two must be /sk/

Whilst /spɹ/ and /stɹ/ are permitted syllable-initially, /spw/ and /stw/ are not permitted syllable-initially in English.

Most languages do not allow as many as three consonants in the syllabic onset however there are some that allow up to six.

Restrictions in the coda are often the mirror image of those in the onset, eg pl ~ lp due to the sonority principle. However there are many exceptions eg /nd/ in "end" but not /dn/.

The number of final consonants in an English rhyme can range from one to four.

eg. /sɪk/ sick, /sɪks/ six, /siksθ/ sixth, /siksθs/ sixths

Languages differ in the structures that they permit. English permits complex codas and onsets. Languages like Hawaiian, for instance, only allow a single consonant in the onset and none in the coda, so every syllable ends in a vowel. Standard Chinese allows only nasal consonants in the coda, so syllables are either open or closed with a nasal.

Phonotactic constraints: combinatory and distributional

Some combinatory constraints in English

- /ŋ/ cannot be preceded by long vowels or diphthongs

- /tʃ, dʒ, ð, z/ do not cluster

- /ɹ, w, l/ only occur alone or as non initial elements in clusters

- /ɹ, h, w, j/ do not occur in final position in Australian English, but /ɹ/ can occur in final position in rhotic dialects such as American English.

- in final position only /l/ can occur before non-syllabic /m/ and /n/.

Some distributional constraints in English

- /ŋ/ cannot occur word initially

- /e, æ, ɐ, ʊ, ɔ/ cannot occur word finally

- /ʊ/ cannot occur initially

- /ʒ/ only occurs initially before /ɪ, iː, æ, ɔ/ in foreign words such as genre.

Defining non-words using phonotactic constraints

We can define two kinds of nonword monosyllables

Accidental gaps

These are phonotactically legal word-like sequences, but happen not to occur in that language

eg. /stremp/ in English is an accidental gap because /stɹ/ is legal (as in "string"), /emp/ is legal (as in "hemp"), but /stɹemp/ happens not to be a word.

Illegal syllables

These violate a phonotactic constraint in that language.

eg. /knep/ is illegal in English because no words can start with /kn/. In German, this would be an accidental gap since /kn/ does occur (‘Knoten’, ‘Kneipe’ etc.).

Maximum onset principle

Phonotactic constraints in the onset are sometimes used to syllabify polysyllabic words under an algorithm known as the maximum onset principle. The problem is as follows. If we have a word like 'athlete', which we know consists of two syllables, where does the syllable boundary occur? The maximum onset principle algorithm works on the basis that as many consonants should be syllabified with a following vowel, providing that the resulting sequence is phonotactically legal. In this case, we have to decide whether /θl/ belongs with the first syllable, the second, or whether /θ/ goes with the first, and /l/ with the second etc.

Based on the maximum onset principle, we would ask:-

(i) Are there any words in English that can begin with /l/?

Yes, e.g. 'leaf', 'lot' etc.

Then assign /l/ to the second syllable.

(ii) Now move one slot to the left: are there any syllables that can begin with /θl/?

No. Therefore, the syllable boundary goes after /θ/ i.e. the word has two syllables, the first of which is /æθ/, and the second of which is /liːt/.

Another example. Syllabify 'constrain' based on the maximum onset principle. Here we have to decide how to break up the medial consonantal cluster /nstɹ/.

(i) Are there any words that begin with /ɹ/?

Yes, 'red', 'range' etc.

(ii) Are there any words that begin with /tɹ/?

Yes, 'train', 'try' etc.

(iii) Are there any words that can begin with /stɹ/?

Yes, 'string', 'strike' etc.

(iv) Are there any words that can begin with /nstɹ/?

No. Therefore, syllabify the word as /kən.stɹæɪn/, where the full stop marks the syllable boundary.

It must be understood that syllable structure is required to satisfy the maximum onset principle only within the limits set by the syntactic, morphological and phonotactic constraints of the language.

eg. “slowlane" vs. “folate"

MOP syllabifies “slowlane" correctly but not “folate".

eg. “incline" vs. “inklike"

MOP syllabifies “incline" correctly but not “inklike".

There are many unresolved issues relating to syllabification.

The foot and word stress

Jonathan Harrington and Felicity Cox

Word stress

In almost all languages, there is a variation in the relative prominence of syllables. This prominence is a function of loudness, pitch, and duration and it is often the change in pitch along with the other factors that is most important. The prominence of syllables is referred to as stress.

Different languages allow for different types of stress patterns. In English the stress pattern of words is fixed to the extent that we can't arbitrarily shift stress around without compromising meaning. The accent falls on the same syllable of the word whenever it occurs (excepting when affixes are added). However, stress placement is also free in that different words can have different stress patterns. This is in contrast to languages like Turkish which has stress on the final syllable of all root forms or Finnish where stress is always on the first syllable. In English, the main accent can be on the first syllable in "answer, sweater, finish, student, photograph", the second in "result, above, around, behind", the third in "understand, politician" or later in words like "articulation, rhoticisation, characteristic".

Word stress and perception

Strong syllables are generally more important for distinguishing between words. For example:

Only 5 out of the 20 Australian English vowel phonemes (/ə, iː, ɪ, ʉː, əʉ/) can occur in weak syllables (see the topic "Broad Transcription of Australian English: Unstressed Syllables" for more information), and of these, schwa occurs with by far the greatest frequency. Therefore, the extent to which unstressed syllables distinguish meaning is considerably reduced compared with stressed syllables.

Compatibly, there is psycholinguistic evidence to show that listeners are much more attuned to/aware of strong syllables (presumably because they are so much more important for understanding what is being said).

Evidence: In reaction time experiments, listeners' responses are much faster to strong syllables.

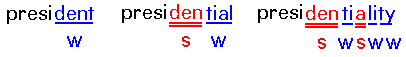

Word stress and the metrical foot

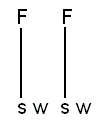

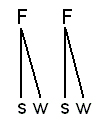

Words are made up of rhythmic units called feet and these comprise one or more syllables. Feet represent the rhythmic structure of the word and are the units that allow us to describe stress patterns.

In each foot, one of the syllables is more prominent or stronger than the other syllable(s) and it is called the strong syllable. It is the head of the syllable. The other syllables in the foot are the weak syllables. In "party", the first syllable is strong and the second syllable is weak.

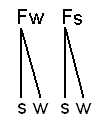

There are two kinds of feet; left-dominant and right-dominant. Languages use either one or the other type.

- Left-dominant feet have a strong first syllable with the following syllables weak.

- Right-dominant feet have a strong final syllable with preceding syllables weak.

English is a left-dominant language. For example, "consultation" has two feet, /kɔn.səl/ and /tæɪ.ʃən/. In each of these feet, the first or left-most syllable is strong and the second is weak, that is, left-dominant.

In each word, one of the feet is stronger than the other feet. Its head is more prominent because it is assigned intonational tone or extra length. This strong syllable has primary word stress and the heads of the other feet have secondary stress.

In "escalator" /eskəlæɪtə/, there are two left-dominant feet and the first has primary stress. The first syllable of the second foot carries secondary stress. The weak syllables are unstressed.

In English there is a tendency for the first syllable of words to be strong and for words not to have adjacent strong syllables. For example, words like "lantern" (s w) and "halogen" (s w w) are far more common than "arise" (w s) or "apex" (s s).

So within feet we can identify a distinction between strong and weak syllables, and within a word across feet we can identify primary, secondary stress and unstressed syllables.

Metrical theory is principally concerned with the parameters that determine the position of stressed syllables in words. Stress is seen as a strength relationship between different syllables.

Building feet into words

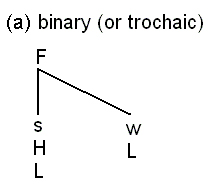

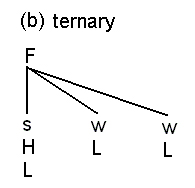

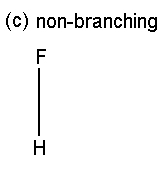

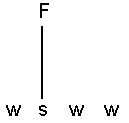

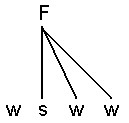

English Words are built from three types of feet.

- binary (trochaic) containing a strong then a weak syllable, eg "elbow"

- ternary containing a strong followed by two weak syllables, eg "oxygen"

- non-branching containing a single strong syllable, eg "cat"

Most words in English have one foot. Obviously all monosyllables are one-footed, but so are also the large majority of two syllable ('pattern') and three-syllable ('Pamela') and even many four-syllable words ('America'). However, many words also have two feet: for example, 'imagination', 'orthodox', 'altitude'. One of these feet is always stronger relative to the other and is marked Fs (strong foot) as opposed to Fw (weak foot). The strong foot always includes the primary stressed syllable while the other weak foot (or feet) includes the syllable(s) with secondary stress. In bipedal words, the order of the feet can be either Fs Fw (i.e., with the strong foot first): these include e.g. 'altitude' and 'orthodox') or they can be Fw Fs (e.g., 'chimpanzee', 'imagination'). There are a few long words with three or more feet: these always have the strongest foot as the last foot (e.g., 'reconciliation' which is Fw ('recon'), followed by Fw ('cili') followed by Fs ('ation').

There are more than a few words in English that begin with a weak syllable. Since feet are left-dominant, and since every foot has to begin with a strong syllable, this will mean that a word-initial weak syllable is unfooted (not associated with a foot). Examples of such initial weak syllables occur in e.g. the first syllable of 'America', 'medicinal', 'pedestrian'.

Words can be built by combining sequentially the above feet, or indeed the feet with themselves. For example, we can have two binary feet ('imagination'), a ternary foot followed by a binary foot ('abracadabra'), a binary foot followed by a non-branching foot ('lemonade'), two non-branching feet ('latex') and so on.

For example (where "(a)" = binary, "(b)" = ternary, and "(c)" = non-branching):-

| (a) + (a) | "economics" |

| (b) + (a) | "abracadabra" |

| (a) + (c) | "matador" |

| (c) + (a) | rare, but possible: "Nintendo" |

| (c) + (b) | very rare |

| (c) + (c) + (c) | impossible |

Because of these constraints and the preference for (a)+(a), strong and weak syllables tend to nearly alternate in English.

This near-alternation of s and w is the basis for our perception of rhythm in English.

Natural speech is highly rhythmic, it tends to have a regular beat. But different languages have different rhythms. In English all feet tend to be of roughly the same length so that feet with more syllables will have relatively shorter syllables than those with fewer syllables. eg abracadabra 2 feet, 1 with three syllables and 1 with 2 but approximately equal duration.

| antidisestablishmentarianism | ||||

| 5 feet, 12 syllables | ||||

| an-ti | dis-est | ab-lish-ment | a-ri-an | is-m |

| s w | s w | s w w | s w w | s w |

Having said this, it is important to note that the stress pattern of natural spoken English is not based on words at all. Phrases like "my dog, the chair, love it", pattern like single words with just one prominent syllable. There is no difference in stress between pairs of words like "arise, a rise" or "ago, a go". Words that begin with unstressed syllables like "above" may have initial unstressed syllable allocated to a preceding foot. eg /IT was a /SIGN from a/BOVE

Stress patterns associated with the foot determine the characteristic rhythm of spoken English. A foot can comprise just a single word or a group of words. In English there are some words that are generally unstressed. They are high frequency, usually monosyllabic function words like "the, a, is, to, and, that". These words can in exceptional circumstances be stressed for particular semantic intent but generally speaking they remain unstressed.

The foot is analogous to the bar in music and spoken utterances consist of a succession of feet in the same way that music consists of a succession of bars. The first syllable of each foot is always strong.

Click here to see an example of the complex relationship between word boundaries, foot boundaries and prosodic phrase boundaries.

Quantity-sensitive feet

In some languages, the choice of primary stress is related to the number and type of segments in the syllable rhyme and this is called quantity-sensitivity. Syllables are considered to be either heavy or light depending on the segmental constituents of the rhyme.

Heavy and light syllables

A light syllable is defined as any (C)V syllable where (C) is zero or more consonants, and where the V is one of /ɪ e æ ɐ ʊ ɔ/ (as in 'hid', 'head', 'had', 'hud', 'hood', 'hod') or /ə/. (The simplest way to remember these vowels is to ask yourself whether there are any open monosyllables with such vowels in English - they are also phonetically quite short). A light syllable also includes (C)VC syllables in word-final position - so the last syllable of 'imagine' is light.

All other types of syllables - that is (C)VC syllables which are not word-final, (C)VCC syllables, (C)V: syllables where V: is any other vowel or diphthong not listed above, or (C)V:C syllables all count as heavy.

What kinds of syllables are metrically weak?

In order to be able to work out the prosodic tree structure for any word, it's obviously important to be able to identify which syllables are strong and weak. This is fact quite easy because, apart from all weak syllables necessarily being Light (see above), the very large majority of weak syllables have a /ə/ vowel, or a vowel that can reduce to schwa (for example, the second syllable of 'minimum' which can be either /ɪ/ or /ə/). There are a few other kinds of weak syllables that don't have a /ə/ as their vowel. These are listed below:

- /iː/ in 'city', 'happy', 'very'. These are metrically weak because in many accents (not Australian) they can be reduced to quite a central vowel. But a clearer indication is given by the realisation of /t/ in words like 'city': certainly in American English, and increasingly in Australian English, it can be produced as an alveolar flap which is voiced and unaspirated (and weakly contacted with the roof of the mouth). And since alveolar flaps can only ever occur in unstressed syllables in English, the syllable in these words is likely to be metrically weak.

- /əʉ/ in words like 'rainbow', 'shadow', 'window'. Word-final /əʉ/ is metrically weak for the same reason as the /iː/ in words like 'city' and 'happy' above. /əʉ/ is often reduced to a centralised monophthong and /t/ can be produced as a flap preceding word final /əʉ/ in words like 'ditto' and 'potato' in some accents.

- /iː/ or /ɪ/ when it precedes /ə/ in words like 'Daniel', 'pedestrian'. This is certainly metrically weak both because it is quite short in duration, and because it can often be produced as a glide /j/, thus, /dænjəl/ is certainly a possible two-syllable production of this word.

- /ʉː/ or /ʊ/ when it precedes /ə/ in words like 'annual' and for the same reason as above: these vowels are very short in duration and can even be deleted resulting in a range of productions from three-syllable /ænjʉːəl/ to two syllable /ænjəl/.

English words of Latin origin (and Latin and Germanic languages) have quantity-sensitive feet. i.e. The phonemic structure of the rhyme contributes to the determination of stress.

For English, non-final syllables with heavy rhymes prefer to be strong.

- Non-final: the syllable is not at the end of the word

- Heavy rhyme: a VC (short vowel + consonant) or V: (long vowel) rhyme

- Light rhyme: a V (short vowel)

These (H) are non-final heavy rhymes and they are strong

These (H) are non-final heavy rhymes and they are strong

Morphology and word stress

English word stress is dependent on:

- origin (Latin and Greek origin have different stress patterns)

- rhythmic factors (as we have seen: In Latin base words non-final heavy syllables like to be strong)

Morphological factors

The position of lexical stress serves to distinguish noun from verb in words like conduct, insert, reject, abstract, convict, object, subject. Stress is on the first syllable of the noun and the second of the verb. For some words stress can also be said to fall on the root word despite the addition of suffixes and prefixes. Board, aboard, boarder; rise, arise, arisen.

However, some suffixes shift stress. Consider:

The suffixes -ion, -ity, -ic, -ify, -ible, -igible, -ish, require stress to be on the preceding syllable

- 'edit, e'dition ('nation, 'ration, ma'gician)

- 'quality, natio'nality

- 'drama, dra'matic, (em'phatic, pho'netic)

- 'terrify, 'justify, i'dentify

- in'credible, 'terrible

- 'negligible, in'telligible

- 'publish, 'finish,'flourish

Words of three or more syllables ending in -ate throw the main accent back 2 syllables eg negotiate, indicate dedicate, whereas words of two syllables ending in ate place the accent on -ate eg translate, dictate, debate.

English word stress parameters: summary

Adequate accounts of English word stress must recognise three relevant factors:

- is largely trochaic (left-dominant) feet

- is quantity-sensitive ie is influenced by the phonemic structure of the rhyme

- is influenced by morphology

There can also be:

- Languages with iambic (right-dominant) feet. The w syllable leads: e.g. an American Indian language Seminole = w s w s, two iambic feet

- Many quantity-insensitive languages. E.g., Warlpiri, an indigenous Australian language, takes no account of whether the rhyme is heavy or light in assigning stress

- Languages like French in which morphology does not influence stress.

Building a prosodic word tree

Here are two examples of how to build a prosodic word for the words 'Turramurra' and 'pedestrian'.

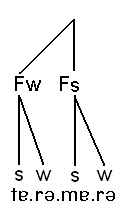

Example 1: "Turramurra"

(1) Begin by identifying whether there are any syllables that are schwa vowels, or which can reduce to schwa, because these have to be metrically weak: for this word, this applies to the second and fourth syllables. Confirm that the other syllables cannot reduce to schwa. If this is the case, they are likely to be metrically strong. We therefore have four syllables which are s w s w.

(2) Join a foot node to each strong syllable. This gives:

(3) Associate any weak syllables with the foot that precedes them. As a result of this, we get two binary feet:

(4) If there is more than one syllable, one of the feet has to marked strong, and the other(s) as weak. The foot that is marked strong is the one that dominates the primary stressed syllable (the third syllable in this example). So the first foot is weak. We therefore arrive at:

(5) Join up the feet to form word tree. If there is an initial weak syllable (doesn't apply in this case, but it would in e.g. 'asparagus') join that to the word level. We therefore have the following with the transcription included:

Example 2: "pedestrian"

Draw a prosodic word tree for 'pedestrian'. Following through the above five steps.

(1) 'pedestrian' = w s w w

(2)

(3)

(i.e. a ternary foot)

(4) This won't apply because there's only one foot.

Summary

Sequences of segments in language are organised into syllables based on the sonority principle. Syllables may be either weak or strong depending on their prominence relative to other syllables in an utterance. Prominence is a product of duration, loudness, vowel quality and pitch change. A syllable contains an onset and a rhyme made up of a peak and coda. The peak is the most sonorous sound in the string and is usually a vowel. Syllables are organised according to the sonority principle with most sonorous components at the centre and least sonorous components at the syllable margins. Syllables join together sequentially to form feet. A foot is a rhythmical unit usually containing two syllables, one weak and one strong (the head). English is a left-dominant language where the left-most syllable of a foot is usually strong and the following syllable(s) are weak. Feet can be monosyllabic eg "dog" (s), disyllabic (sw) eg "city" or ternary (sww) eg "oxygen". Longer words are constructed from combinations of these three foot types.

Words are made up of feet. A word can have one or more feet. If a word has a single foot it will have primary word stress in citation form. If a word has more than one foot, the strong syllable of one of the feet will have primary stress and the strong syllable of the other feet will have secondary stress. The choice of syllable for stress attachment will depend on the individual rules of the language but some languages such as English are quantity sensitive in that the number of elements in the rhyme help to determine which syllable will be stressed. If a rhyme has a short vowel + consonant or a long vowel the rhyme is said to be heavy. If the rhyme has just a short vowel, the rhyme is said to be light. In English non-final syllables with heavy rhymes prefer to be strong. However, the origin of a word and also its morphology are important factors in determining stress placement in English.

Additional reading

Students should also read the following: Clark, Yallop & Fletcher (2007) (Sections 3.1, 3.11, 9.3, 9.6, 9.7, 11.13)

Content owner: Department of Linguistics Last updated: 12 Mar 2024 9:29am