Introduction to phonology

Phonology: The study of the sound structure of language

Jonathan Harrington

Important: You must have installed the phonetic font "Charis SIL" or tested this installation to determine if the phonetic characters installed properly.

Does language have structure?

If there were no structure, then:

- we would have to memorise lists of utterances

- there would be no units into which utterances can be decomposed

- utterances would be unrelated to each other.

What kinds of structure?

Units that are:

- paradigmatically opposed to each

- syntagmatically related to each other.

Paradigmatic contrasts

Units that are paradigmatically opposed to each other belong to different classes that function in different ways.

E.g. words belong to paradigmatically contrasting grammatical classes.

We know this by applying a substitution test.

I was happy to _________

learn/leave/wander/relax (verbs)

*underneath/overhead

*student/door/wanderer/relaxation

*energetic/thoughtful/green/sad

(Further details: Tallerman, 1998: Understanding Syntax. Arnold)

Syntagmatic relationships

- the units can be parsed into higher order units in different ways

- the order of units matters

- there can be a multilevelled hierarchy

- there is headedness.

Syntagmatic I: Parsing into higher-order units

"Australian boys and girls love to swim"

could be either:

[Australian boys] and girls love to swim

or:

Australian [boys and girls] love to swim

Syntagmatic II: Order matters

Australian boys and girls love to swim

*Boys Australian and girls to swim love

(note: "*" means that this is not possible)

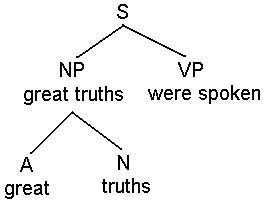

Syntagmatic III: Hierarchical structure

A hierarchical structure means: there are units within units within units...

E.g. a noun-phrase is a unit, and so is a verb-phrase, but together they makeup another unit called a sentence:

| [[Great truths]NP [were spoken]VP]S= |  | |

| …and the unit, noun-phrase, is itself made up of two other units, an adjective and a noun |

Syntagmatic IV: Headedness

Headedness means that one of the units that makes up a hierarchical unit is obligatory. This obligatory unit is the head of the hierarchy.

For example:

- exclamations aside, you can't usually form a sentence without a verb (so the verb is the head of the sentence)

- every noun-phrase must have a noun (so the noun is the head of the noun-phrase).

Phonology – if there is structure to sound then:

Are there units?

What's the evidence that:

- they are paradigmatically contrastive?

- they form syntagmatic relationships?

Phonology: units

In each human language, there are a finite number of units called phonemes that a language uses to build its words.

Animal languages

- They don't have phonemes (no 'building blocks' for words) and so there is a one-to-one relationship between meaning and sound.

Human languages

- phonemes are combined in different, productive ways to produce new meanings e.g., /pɪt/→/tɪp/

- the relationship between meaning and sound is arbitrary.

Phonology: Paradigmatic oppositions I

Words must sound sufficiently distinct (from each other) in order to be understood.

For this to be possible, phonemes have to be chosen from a number of dimensions, or natural classes, that have contrastive values.

Contrastive is in an articulatory and/or acoustic sense. For example, phonemes are often chosen from the natural class Stricture which has contrastive articulatory values (stop/fricative/approximant) which have different acoustic consequences (silence/aperiodicity/low frequency energy)

Phonology: Paradigmatic oppositions II

Languages tend to form phonemes out of natural classes in a highly productive way.

For example:

| Nasality | oral vs. nasal (2) |

| Place | bilabial vs. alveolar vs. velar (3) |

| Maximum number of possible phonemes = 2 x 3 = 6 | |

b | d | ɡ | m | n | ŋ | |

Nasality | -nasal | -nasal | -nasal | +nasal | +nasal | +nasal |

Place | bilabial | alveolar | velar | bilabial | alveolar | velar |

This is one of the reasons why phonemes tend to form patterns:

Language A | ||

b | d | ɡ |

m | n | ŋ |

f | s | |

... is much more probable than:

Language B | ||||

b | ɡ | |||

n | ||||

ʃ | h | |||

Syntagmatic structure

Is there syntagmatic structure in phonology?

- Can phonemes be grouped into superordinate units?

- Does order matter?

- Are there hierarchies? (units within units within units)?

- Is there headedness?

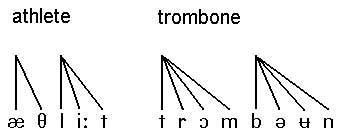

Syntagmatic I: Superordinate units

The simplest evidence that there are superordinate phonological units is that, in almost every language, phonemes are organised into syllables.

Syntagmatic II: Order

In all languages, the order in which phonemes can occur in syllables is restricted.

for example:

In English, /k/ can be followed by /w j l r/ at the beginning of a syllable:

/kwiːn/ ('queen'); /kjʉːt/ ('cute'); /kliːn/ ('clean'), /kriːp/ ('creep').

But there are not many words in English that can begin with /pw/,/bw/,/tl/,/dl/.

And although approximants can follow some oral stops, /w r l/ can't follow nasals: /nw/,/nl/,/nr/ don't occur.

Syntagmatic III: Hierarchy

- Utterances are made up of one or more intonational phrases.

[When I get to Sydney] [I'll visit Emily]

- Every intonational phrase is made up of one or more words

You could have an intonational phrase as small as one word. For example:

| [Stop!] | S | [Adelaide] [is in South Australia] |

- Every word is made up of one or more syllables.

- Every syllable is made up of one or more phonemes.

Syntagmatic IV: Headedness

Is one of the units at each level of the hierarchy obligatory?

Intonational phrase

Every intonational phrase has to have a tonic syllable. The word containing the tonic syllable is often called the nuclear accented word.

Word

Every word has to have a primary stressed syllable.

Unstressed syllables are optional ('pat', 'John', 'said')

Secondary stressed syllables are possible ('imagination'), but optional ('America')

Syllable

Every syllable has to have a nucleus which is a vowel, or vowel-like sound

Initial consonant(s) are optional ('opt', 'each', 'own')

Final consonant(s) are optional ('free', 'say', 'do')

Conclusions

There is structure to the sounds of language. In phonology, we want to find out what this structure looks like as well as how it differs across languages.

Evidence for structure

There are units (phonemes, syllables, words, intonational phrases)

There is paradigmatic contrast (e.g. oral vs. nasal phonemes)

There is syntagmatic structure:

- phonemes are sequentially grouped or parsed into syllables

- there are restrictions on the sequential order of phonemes in a syllable

- there are multiple hierarchies

- there is headedness.

Content owner: Department of Linguistics Last updated: 12 Mar 2024 9:18am