Intonation - transcribing with ToBI

Transcribing Intonation

Jonathan Harrington

Important: You must have installed the phonetic font "Charis SIL" or tested this installation to determine if the phonetic characters installed properly.

Acknowledgement

Many of these examples are from 'Guidelines for TOBI labeling' by Mary Beckman and Gayle Ayers.

Introduction

The object of this tutorial is to introduce you to some of the main components of transcribing intonation in English.

There are three main parts to consider when transcribing intonation: dividing an utterance into one or more prosodic phrases; deciding which word is the nuclear accented word and which of the remaining words in the utterance are accented or unaccented; and finally assigning a tune, consists of one or more pitch accents and a boundary tone to each prosodic phrase.

Prosodic phrases

Every utterance has one or more prosodic phrases (even if you say only a single word, that will still count as a prosodic phrase). Most of the examples with which you will be presented will consist of only a single prosodic phrase. We can denote the boundaries of prosodic phrases with square brackets, thus:

[Peter saw Mary].

[Did you see Peter?]

[Peter!].

An example of an utterance that would almost certainly have to consist of two prosodic phrases is as follows:

[when I get to Sydney,][I'll go an visit John]

and in this example 'Sydney' would typically have a fall-rising (continuation-rise) intonational contour.

You can hear the boundaries between prosodic phrases because:

- this is where the speaker sometimes slows down

- you might hear an abrupt change in the pitch

- the last syllable of each prosodic phrase is typically quite long

Accented words

Every prosodic phrase has to have at least one accented word and it may (and usually does) have unaccented words. So the next thing to try to do, after you have decided how many prosodic phrases there are, is to decide which of the words in each prosodic phrase are accented and which are unaccented. There are two main ways of doing this. By listening to the utterance: accented words sound more prominent and are sometimes louder than unaccented ones. The greater prominence of accented words comes about partly because, all things being equal, they are often longer than unaccented words, and are acoustically higher in intensity. But the main reason is because there is a pitch-accent associated to each accented word which can produce quite dramatic pitch changes in the vicinity of the accented word's primary stressed syllable. There are two main kinds of pitch accent. A H* (high-star) pitch accent which tends to produce a pitch peak. And an L* (low-star) pitch accent which produces a pitch trough.

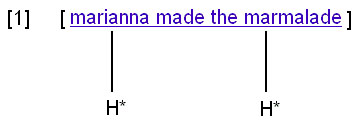

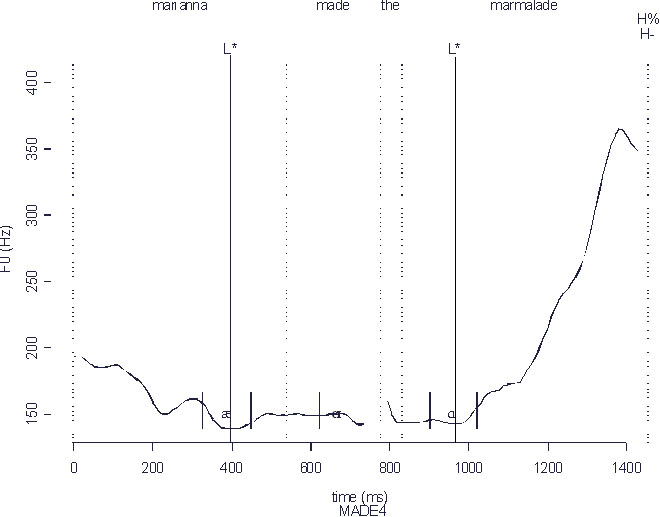

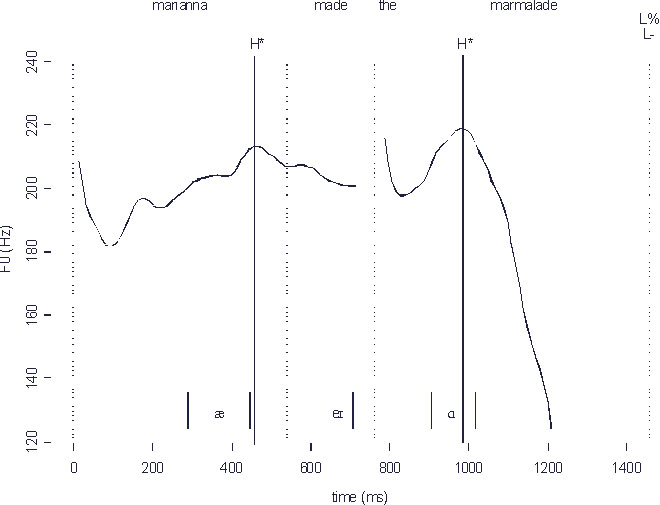

For example, have a look at the pitch contour of [1] 'marianna made the marmalade', in the audio file below.

Both 'marianna' and 'marmalade' are accented whereas 'made' and 'the' are unaccented. Notice the pitch peaks on the primary stressed vowels of these words: on the [æ] of 'marianna' and the [ɑ] of 'marmalade'.

These pitch peaks are the acoustic consequences of aligning the H* pitch accents to these words (which makes them accented). We can denote this as follows in the audio file below:

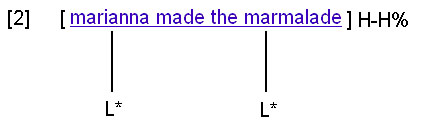

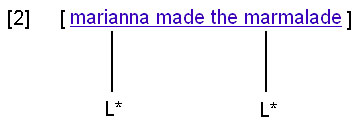

[2] below shows a typical intonational contour for a 'yes-no' question (one that requires an answer of 'yes' or 'no'). In this case, we have two L* pitch accents on the same words and there is a pitch trough in their primary stressed vowels. So we would denote this as:

Nuclear accented word

The last accented word in any prosodic phrase is known as the nuclear accented word and it often sounds more prominent than other accented words in the same prosodic phrase. In both of the above examples, 'marmalade' is the nuclear accented word. One of the reasons why the nuclear accented word is particularly salient is because there is very often such a dramatic change in pitch from the pitch accent with which it is associated to the boundary tones discussed in the next section.

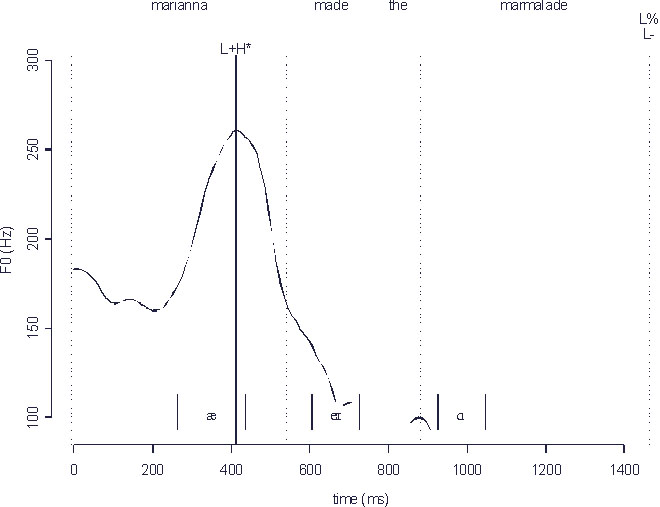

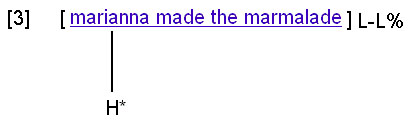

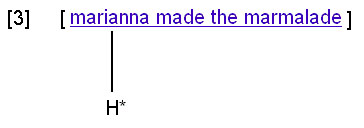

Sometimes the nuclear accented words can occur early in the prosodic phrase, which often has the effect of marking a word as especially prominent. An example is sentence 3 (compare its pitch contour with sentence 1) in which there is an H* pitch accent on the first word, then a fall in pitch due to the boundary tones. But note that there is no other word which is marked by a pitch accent. You can listen to this in the audio file below:

We would represent the pitch-accent of 3 as:

from which we can immediately see that 'Marianna' is the nuclear accented word and all other words are unaccented (there could not be any other accented words since the nuclear accented word is always the last accented word in the prosodic phrase; therefore, if the nuclear accented word comes first, then all following words in the same prosodic phrase must necessarily be unaccented).

Boundary tones

These are the other part of the tune and they are associated with the right edge of the prosodic phrase (so we write them after the ] boundary). In conjunction with the tone target of the nuclear accented word, they are responsible for perhaps the most salient part of the intonational contour. We will consider four kinds. In all cases, they affect a particular interval of intonation: from the pitch accent of the nuclear accented word to the end of the prosodic phrase. Here are the four kinds.

L-L% (low) boundary tone

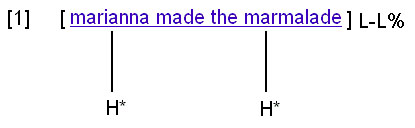

This is a common in 'neutral' declarative sentences. The L-L% boundary tone causes the intonation to be low at the end of prosodic phrase. Therefore, the intonation will fall sharply from the H* pitch accent of the nuclear accented word to the end of the prosodic phrase. (You very rarely get tunes which have an L* nuclear accented word in an L-L% phrase).

You can hear a typical example of an L-L% boundary, in the first sentence considered earlier, in the audio file below (sentence 1):

It is very clear to see how the pitch falls from the [ɑ] of 'marmalade' through the rest of the word to the end of the phrase.

The association of this tune to the text is as follows:

H-H% (high) boundary tone

This is very common in 'yes-no' questions. It is also a common feature of Australian English declaratives and is known as the high-rising-terminal. It causes the pitch to end high at the phrase boundary and it very often co-occurs with an L* nuclear accented word. As a result, the pitch rises dramatically from the nuclear accented word's pitch accent to the end of the phrase.

You can hear a good example of this in the yes-no question in [2]:

The tune in this case is:

L-H% boundary tone

This is known as a continuation rise. It can occur in a number of contexts, but it often gives the impression that the speaker still has something left to say. For example, the first phrase of [When I get to Sydney], [I'll go and visit John] would very often have an L-H% type of boundary tone. The effect on the pitch contour is as follows: first it will drop to a low value and then it will rise towards the end of the prosodic phrase. Therefore, if the pitch accent of the nuclear accented word is H* (as it very often is in this context), the pitch contour over this interval firstly falls to a low value, and then typically stays low until the end of the prosodic phrase where it rises (but not as much as in an H-H% phrase). So over this interval, the pitch goes down and then up again.

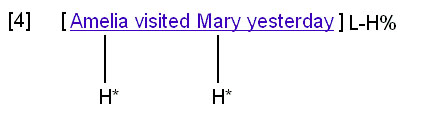

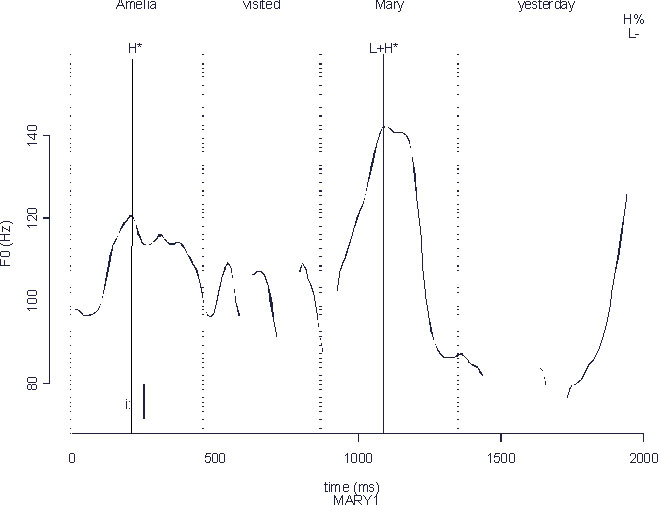

You can hear a good example of this boundary tone in the audio file [4] Amelia visited Mary yesterday, below.

This prosodic phrase has two accented words, 'Amelia' and 'Mary' and so 'Mary' is the nuclear accented word. Notice how the pitch falls on 'Mary', then stays low over the first part of 'yesterday', and then rises at the end of the prosodic phrase.

We can annotate this as follows:

So in summary, the shape of the pitch contour from 'Mary' to the end of the phrase is falling and then rising.

H-L% boundary tone

This is perhaps the least common boundary tone. It sometimes occurs in a somewhat bored recital of lists, and can generally lend a 'disinterested tone' to the utterance. The effect on the pitch contour is as follows: after the pitch accent of the nuclear accented word, the pitch stays quite high and then falls at the end of the prosodic phrase (but not as dramatically as in an L-L% phrase).

Early placement of nuclear accented words

When the nuclear accented word occurs early in the prosodic phrase, the relationship between the boundary tone and the pitch contour is the same: the boundary tone controls the shape of the pitch contour between the pitch accent of the nuclear accented word and the end of the prosodic phrase. Therefore,

when the nuclear accented word occurs early in an L-L% phrase, the pitch contour falls immediately after the nuclear accented word and then stays low until the end of the prosodic phrase - as in the earlier example of 3., which was:

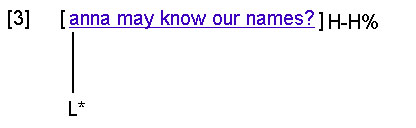

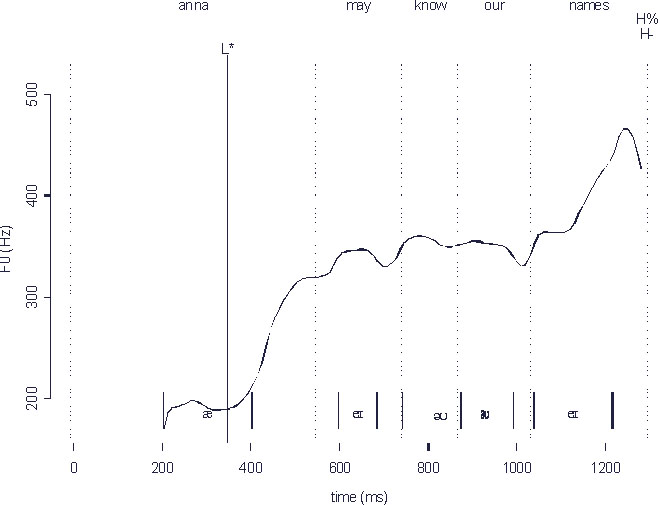

An example of an early nuclear accent placement in an H-H% is [5], Anna may know our names?, as heard in the audio file below:

So in this case, the H-H% boundary tone controls the shape of the entire pitch contour from the L* low tone to the end of the phrase, causing it to rise continuously from the pitch trough (associated with the L*) to the end of the prosodic phrase.

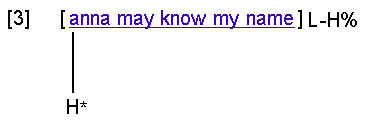

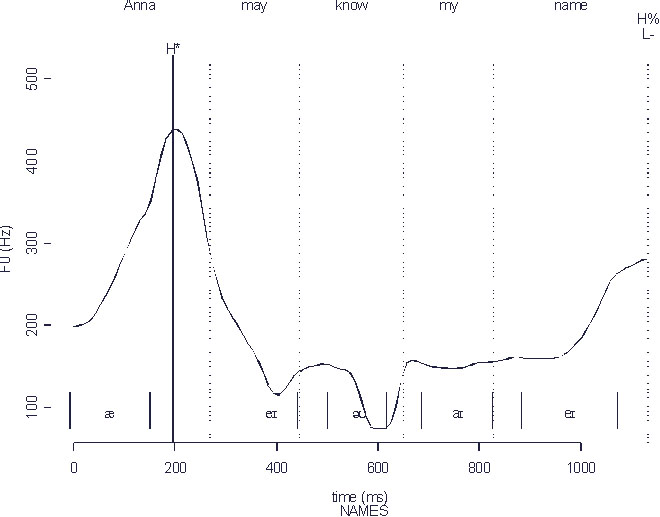

When the nuclear accented word occurs early in an L-H% phrase, the pitch stays low throughout almost the entire remainder of the prosodic phrase after the nuclear accented word and then only rises at the end of the phrase. An example of this can be heard in the file below, [6] Anna may know my name, with an H* pitch accent on 'Anna'. In this case the boundary tone causes the pitch contour stay low after 'Anna' and it only rises again at the end of the prosodic phrase.

Content owner: Department of Linguistics Last updated: 12 Mar 2024 9:47am