Engineering Senior Lecturer Dr David Inglis weighs in with his thoughts on the age of artificial intelligence.

The forklifts at the local Coca-Cola factory drive themselves, and Uber is testing driverless taxis in the USA. Robots and artificial intelligence are taking jobs. So, when the housing boom ends, our children might again dream of owning a home, but will there be any jobs for them?

One of my favourite examples of just how much we can gain from technological advance comes from Yale economist Bill Nordhaus and his research into the amount of light a person could buy with a day’s wage. Four thousand years ago, you could get just 10 minutes with a state-of-the-art beef tallow candle. Whale oil was the next big thing, and by 1850 you could spend a day’s wage on a whole hour of light.

The scientific discovery and production of kerosene was a solution that both saved the whales and brought light to the masses – a day’s wage would buy you five hours. Over the next 150 years, science and technology led to the efficient generation and transport of electricity as well as steady improvements in light bulbs. Today, you could buy over 20,000 hours.

This technological progress has benefited the vast majority of humans alive today and is one of the reasons we can effectively treat most diseases, but also why we have time to take a vacation. Yes, the whalers and candle makers lost their jobs, but the benefits to the many far outweigh this and we shouldn’t expect research and development today to be any less transformative.

Most of us understand this, so why are we afraid of robotics and artificial intelligence? Why aren’t they viewed like any other technology that will lift productivity? Granted, autonomy in a machine can be somewhat disturbing, and a little reluctance toward self-driving cars is normal, however it is not without precedent. Elevators used to be driven by people, for example. Imagine how frightening it would have been to step into one of the first automated elevators, willingly locking yourself in a metal box with just a few buttons for floors and a red help button.

This is a model for the truly revolutionary driverless cars of the future – no steering wheel or brake, just a digital map and a red emergency stop button. If legislation doesn’t lag behind the technology, we can look forward to sleeping during our commute in the near future. However, getting there means we cannot require that all technology be perfect before being adopted. Accidents will happen, software updates will be required, and insurance companies will price the risk accordingly. Of course, in the long run, it will be far cheaper to insure a fully automated car than an 18-year-old P plater with all their human error.

Most robotic developments aim to work with humans. When Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov, we didn’t stop playing chess, and now the best chess in the world is played by teams of humans and computers. They are complementary and the combination of human and computer has consistently delivered the best results. In the not-too-distant future, the fastest cars and the safest surgeries will be operated by humans working with computers.

Sometimes though, it will even be safe enough to let the computer take over. So, whether welder or radiologist, a computer or machine might one day compete with us all. Many people will find new and different work, but the amount of employment will always be under pressure from automation. The consequences of this can be bad. When an automated forklift runs the floor at a warehouse, or you book your holiday on a website, wealth shifts from you to whomever owns the robot, and this makes a small contribution to economic inequality.

Cheap communication, free information, and quality education have allowed huge numbers of innovators and entrepreneurs to create value with little capital. Their actions challenge established power and reduce inequality while raising productivity.

To keep this going, we must continue to support the free flow of information by supporting the NBN and net neutrality. The education that we offer must provide the basis for innovation by teaching and applying STEM and, in particular, coding. With the proliferation of microprocessors in everyday objects like home appliances and cars, software surrounds us. Wired magazine even predicted that coding would be the next big blue collar job.

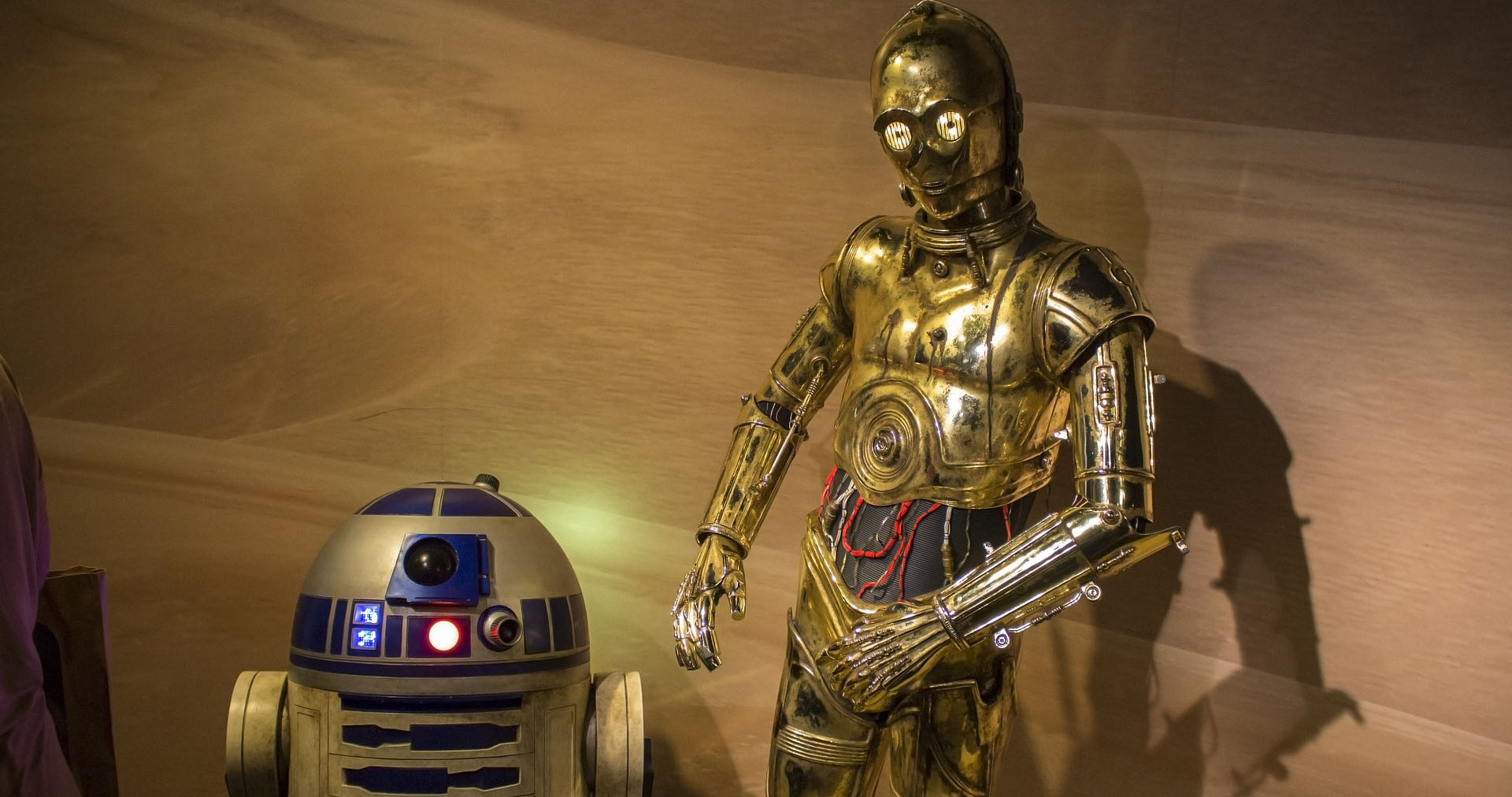

Movies and television have given us many scenarios where the future is bleak, so how do we end up with the utopian Star Trek instead of the haves and have-nots of Star Wars? Education, which must teach STEM, must also help us understand each other. And governments must re-distribute wealth while promoting economic and/or community participation. What unites the dystopian futures isn’t technology, it’s the destruction of our social fabric. Technology will not ruin us, but greed and corruption might.

Back to homepage

Back to homepage

Comments

We encourage active and constructive debate through our comments section, but please remain respectful. Your first and last name will be published alongside your comment.

Comments will not be pre-moderated but any comments deemed to be offensive, obscene, intimidating, discriminatory or defamatory will be removed and further action may be taken where such conduct breaches University policy or standards. Please keep in mind that This Week is a public site and comments should not contain information that is confidential or commercial in confidence.