Manichaean and (Nestorian) Christian Remains in Zayton (Quanzhou, South China) ARC DP0557098

Compiled by Professor Sam Lieu FRHistS, FSA, FAHA and Dr Ken Parry

Fig. 1. Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill near Quanzhou. (C1, photo M. Wilson 2004)

Project History

Since 2000 a research team of Australia-based scholars has systematically collected and analysed finds by Chinese arcaheologists and scholars relating to the diffusion and cultural adaptation of two religions of Near Eastern origin, Manichaeism and Christianity, which had reached China via the Silk Road in the Middle Ages.

The project focuses particularly on Manichaean and Nestorian remains found in the port city of Quanzhou (Ch'üan-chou, viz. the Zayton of Marco Polo) which was a thriving multicultural centre throughout the Middle Ages. The team is led by Professor Sam Lieu FSA, FAHA (Macquarie) and consisting of Dr Ken Parry (Macquarie), Professor Majella Franzmann FAHA (UNE), Associate Professor Iain Gardner FAHA (Sydney) and Dr Lance Eccles (Macquarie) with Ms Michelle Wilson (Macquarie) as project photographer in 2004.

The team is supported at an international level by Professor Aloïs van Tongerloo FRAS (Leuven) and Professor Nicholas Sims-Williams FBA (SOAS London and AIIT Cambridge). The project is funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC DP0210152 2003-04 and DP0557098 2005-09) and the Chiang Ching Kuo Foundation of International Scholarly Exchange (2001-08) and operates under the aegis of the UNESCO-sponsored Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum Project.

Quanzhou (Ch'üan-chou)

The City of Quanzhou

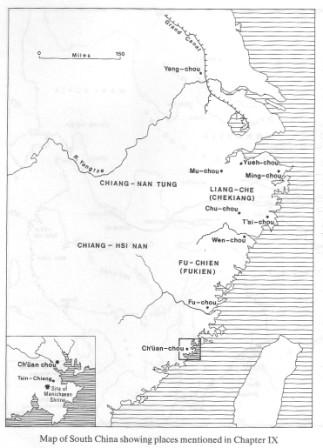

The modern port-city of Quanzhou (Ch'üan-chou in the older Wade-Giles system of transliteration) is one of the principal cities of the province of Fujian on the South China coast. As the map below (Fig. 2) shows, it is strategically situated on the Taiwan (Formosa) Straits and within easy reach of all the major cities of China via a net work of postroads and canals.

Fig. 2. Map of main Manichaean sites in China from S. Lieu, Manichaeism (Manchester: Manchester University Press 1985)

Quanzhou has a complex adiministrative history and is known by a number of names throughout the pre-Modern Era. The Quanzhou Prefecture was established in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). During the Yuan when China was under Mongol rule, a Maritime Trade Commission was established in the port in AD 1277.

The city was better known to visitors from the Middle East and from Europe as Zayton or Zaitun (Latin Cayton). The fact that this better known name did not appear to be phonetically related to the Chinese name of the port-city has long caused problems of identification for researchers until it was realized that the western name (probably of Arab origin) was transliterated from the citong - Chinese for the Paulownia tree which once adorned the city's walls in the Middle Ages. In Arabic zayton is the word for "olive" and the famous traveller Ibn Battuta from Tangiers lamented the total lack of olives there.

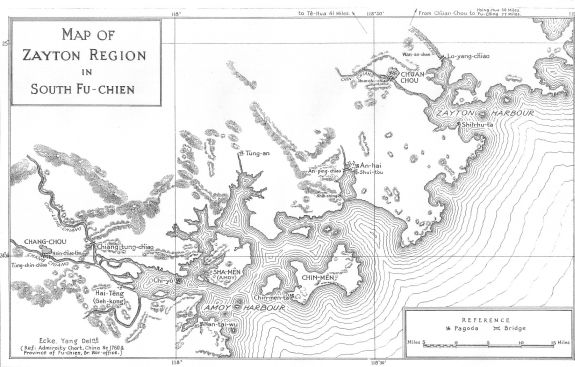

In the modern period, the British Government, anxious to establish a coaling-station for its China fleet somewhere between Hong Kong and Shanghai, established the port city of Xiamen (Hsia-men, popularly known in the West as Amoy) in the course of the 19th Century. The next map (Fig. 3) shows clearly the relationship between the two port cities.

Quanzhou had by then declined in importance as a river-port because of progressive silting of its harbour. Gone were the days when hundreds of ocean-going sailing vessels moored in its famous harbour carrying precious cargos from as far afield as Alexandria as witnessed to by Marco Polo who departed from China via Quanzhou (Zayton) c. 1292.

Fig. 3. Map of Zayton Region from G. Ecke, The Twin Pagodas of Zayton (Cambridge, MA)

The same region shown in the map aboe is well depicted in a relief model now in the Quanzhou Museum of Overseas Maritime Connections (Quanzhou Maritime Museum for short). Note that the medieval city which is situated on the top right-hand corner of the map was walled.

Fig. 4. Model of Quanzhou on display in the Quanzhou Maritime Museum. (Photo S. Lieu, 1990)

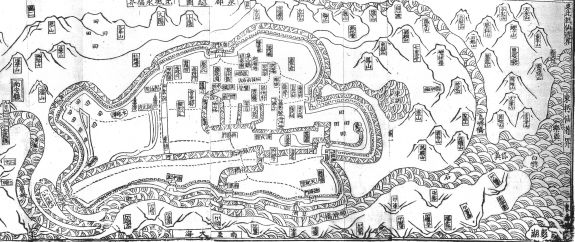

An old map compiled in the Qing Dynasty c. 18th C. (Fig. 5) shows particularly clearly the medieval walls of the city.

Fig. 5. Old diagrammatical map of Quanzhou from Ecke, op. cit.

It was the progressive demolition of these medieval walls in the period between the two World Wars in the 20th Century which led to the finds which form the main source of study for this research project. There is now no problem identifying Quanzhou with the Zayton of Marco Polo as a number of inscriptions found in Quanzhou and studied by the team contain the western/Middle Eastern name of the city (Zayton in Syro-Turkic and Cayton in Latin - see below commentary to Figs. 20 and 26).

For further information on Quanzhou see the excellent website:

http://courses.washington.edu/quanzhou/vernac/quanzhou/qzintro.htm

Manichaeism or the Religion of Light (Mingjiao) in the Quanzhou region (part 1)

Founded by the self-style prophet Mani (AD 216-276) in the part of the then Persian Empire which comprises modern Iraq, the Manichaean religion drew its inspiration from Judaeo-Christianity, Gnosticism and Zoroastriansim. Mani was a fervent evangelist and from the Fourth Century AD onwards his religion enjoyed great missionary success, especially in the cities along the Silk Road.

In the 8th C it became the state religion of the Uighur Turks whom the Tang government in China relied as their principal mercenaries to fight their frontier wars. Under the patronage of successive Uighur Khaghans, Manichaean monasteries were established in the principal Chinese cities north of the River Yangtze. It was severely persecuted in the 9th C and the religion survived mainly in the region of Turfan, especially around the Uighur capital of Chotcho until the 11th C and in the province of Fujian in South China up to the turn of the 20th C.

Western scholars were first alerted to the possible survival of Manichaean remains in the vicinity of Quanzhou with the publication of a major article by the French Sinologist Paul Pelliot in 1934 ('Les traditions manichéennes au Fou-kien', T'oung Pao 22 (1934) 193-208). In it he drew attention to the notice by the Chinese scholar Chen Yuan to the material contained in one of the most important local histories of Fujian (the Minshu by He Qiaoyuan) on the existence of a Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill which is in the sub-prefecture of Jinjiang about 11 km south-east of Quanzhou. The relevant part of He Qiaoyuan's account reads:

The Huabiao Hill of the county of Jinjiang prefecture of Quanzhou is joined to the Lingyuan Hills. Its two peaks stand up like huabiao (i.e. twin columns placed at entrance of tombs). On the ridge slope back of the hill is a cao'an (lit. thatched nunnery) dating from the Yuan period. There reverence is paid to Buddha Mani. The Buddha Mani has for name 'Brilliant Buddha Mo-mo-ni'. He came from Sulin (i.e. Assuristan) and is also a Buddha, having the name 'Envoy of the Great Light, Complete in Knowledge'.... In the period Huichang (841-846) when (Buddhist) monks were suppressed in great numbers, the religion of the light was included in the suppression. However, a Hulu fashi (a very distinctive title of a Manichaean priest) came to Futang (south of Fuzhou), and taught his disciples at Sanshan (in Fuzhou). He came to the prefecture of Quan in his travels and died (there) and was buried at the foot of a mountain to the north of the prefecture.

In the period Chidao (995-997) a scholar of Huai'an, Li Dingyu, found an image of the Buddha (Mani) in a soothsayer's shop at the capital; it was sold to him for 50,000 cash-pieces, and this his auspicious image was circulated in Fujian. In the reign of Chenzong (998-1022) a Fujian scholar, Lin Shih¬chang, presented his (i.e. Manichaean) scriptures for sake-keeping to the Official College of Fuzhou. When Taizu of the Ming Dynasty established his rule, he wanted the people to be guided by the Three Religions (i.e. Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism). He was further displeased by the fact that [the Manichaeans] in the name of their religion (i.e. Ming) usurped the dynastic title. He expelled their followers (from their shrines) and destroyed their shrines. The President of the Board of Finance, Yu Xin, and the president of the Board of Rites, Yang Lung, memorialized the throne to stop (this proscription); and because of this the matter was set aside and dropped. At present those among the people who follow its (Manichaean) practices use formulas of incantation called 'The master's prescription', (but) they are not much in evidence. Behind the shrine are the Peak of Ten Thousand Stones, the Jade Spring, the Cloud-Ladder of a Hundred Steps, as well as accounts inscribed on the rocks (by visitors).

Chen Yuan, the discoverer of this text published it in an article in 1923 and Chinese scholars began almost immediately to locate the shrine using the detail geographical information provided by He Quiyuan's account. However, China was embroiled in Civil War throughout the 1920's and from 1938 to 1945 much of coastal Fujian was occupied by Japanese forces. A group of scholars from the University of Xiamen tried to locate the building in 1928, but were turned back shortly after leaving the city of Quanzhou because of the presence of armed bandits in the vicinity.

The first notice Western scholars received about the successful location of the shrine was the publication of the important work on foreign religious inscriptions (Islamic, Nestorian, Catholic and Manichaean) of the Quanzhou region by a local archaeologist and school teacher called Wu Wenliang in 1957 (Quanzhou zongjiao shike (Religious Stone Inscriptions at Quanzhou), Beijing).

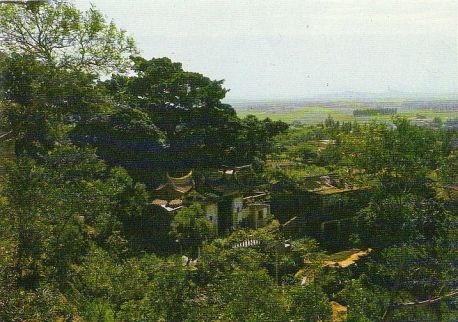

The work contains three photographs relating to the shrine and for the next two decades, as China was caught up in the Cultural Revolution and largely closed to the outside world, these three photographs remained the only published physical evidence of the shrine. However, in 1980, a guide-book to the historical remains and scenic sites of Quanzhou was published in Fuzhou (Quanzhou mingsheng guji - Scenic Spots and Historical Sites in Quanzhou, compiled by a committee) containing a colour photograph giving a panoramic view of the shrine prior to modern developments.

Fig. 6. View of the Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill in Jinjiang prior to modernization.

(Photo taken c. 1980 - from Quanzhou mingsheng guji).

The shrine is styled a cao'an in Chinese which literally means a "thatched nunnery" and is still used as a place of Buddhist worship by local village folk and staffed by a small number of nuns. It was built against a cliff-face and dominating the back wall is a statue of Mani as the Buddha of Light.

Fig. 7. Statue of Mani (C2) from Wang Lianmao, Return to the City of Light (Fuzhou, 2000) p. 130.

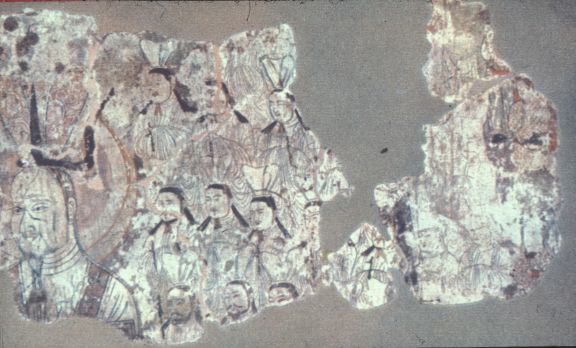

Measuring 1.54 (h) x 0.85 (w) 0.11 (d) m, the statue exhibits a number of typically Manichaean features and in particular the symbol of two knots. The local Manichaeans were nick-named the followers or sons of the "Two Knots" during the Song period. The garment also manifest a number of details similar to those worn by a Manichaean leader and his followers as shown on a wall-painting which was removed by Albert von Le Coq from a Manichaean site in Chotcho in Central Asia to Berlin where it was sadly destroyed by Allied bombing during the Second World War (Fig. 8).

Manichaeism or the Religion of Light (Mingjiao) in the Quanzhou region (part 2)

Scholars have noted that the visage of the statue is different from that of the Buddha as normally depicted in statues or paintings in the Far East. The cheeks of the Mani-figure are fleshy and his eyebrows are raised. He is also bearded and his lips are exceptionally thin. The head of the statue was said to have origially exuded a moustache or side-burns but these were had been knocked off by a zealous Buddhist monk over half a century ago to make the statue more 'Buddha-like'

Fig. 8. Wall painting of a Manichaean Leader nd followers from Chotcho.

(From A. von Le Coq, Chotscho, Ergebnisse der kgl. Preussischen Turfan Expeditionen, Berlin, 1913, Fig. 1)

Also worth noting is that the sleeves of the garment depicted on the Mani statue at Jinjiang exhibits distinctive squares which could, as Dr Jorinde Ebert has recently shown in her study ('Segmentum and Clavus in Manichaean Garments of the Turfan Oasis' in D. Durkin-Mesiterernst et al. (eds), Turfan Revisited: The First Century of Research into the Arts and Cultures of the Silk Road (Berlin 2004) 72-83), were originally badges of rank (segmenta) worn by officials in Late Antiquity. This is also depicted on a seated figure during the Bema Feast in a Manichaean miniature from Chotcho (MIK III 4979 in Z. Gulácsi, Manichaean Art in Berlin Collections (Turnhout 2001) 71).

The halo effect behind the statue is also uncommon for a Buddha-statue in China, but in Central Asia it is found with Buddhas associated with Light. The painstakingly accurate non-Buddhist features of the statue of Mani bears out He Qiaoyuan's statement that the sect in Quanzhou took the trouble to locate an original statue of Mani in a curio shop in one of the northern capitals of China in which Manichaeans from Central Asia were well established during the Tang Dynasty.

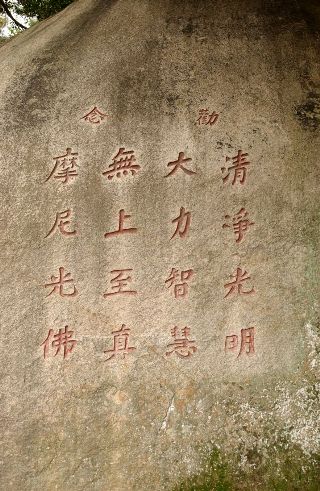

In front of the shrine was once an inscription of sixteen Chinese characters on a large natural rock in four rows follow by the date.

Fig. 9. Manichaean inscription AD 1445 (now destroyed) (C3, from Wu Wenliang, Quanzhou zongjiao shike (Beijing, 1957, fig. 106).

In translation they read:

(You are) implored to comemorate (or recite):

Purity, Light,

Great Power, Wisdom,

the highest and unsurpassable truth,

Mani the Buddha of Light.

(Inscribed in) the ninth month of the Jichou year of the Zhengtung period (i.e. AD 1445).

Manichaeism or the Religion of Light (Mingjiao) in the Quanzhou region (part 3)

The text shows indubitably that the shrine was once Manichaean as the four attributes "Purity (i.e. divinity), Light, Power and Wisdom" are those of the Father of Greatness in the Manichaean pantheon as given in Mani's Living Gospel which we find cited in a Chinese Manichaean text found in Dunhuang in Chinese Central Asia. Sadly this important inscription was destroyed by zealous Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. The text has now been reinscribed but on a cliff-face to the side of the shrine (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Reinscribed version (minus date) of the inscription. (C3r, photo M. Wilson, 2004)

As shown on the first illustration, buildings were added to the shrine after the Cultural Revolution (cf. Figs. 1 and 6). A pavilion on stilts was added to the front of the shrine with seating for visitors (esp. tourists) and most importantly a major Buddhist temple complex was added on the hillside below the cao'an. The construction of the latter was preceded by archaeological excavation by the Jinjiang Museum and one of the most spectacular finds was a complete brown glazed bowl once used by the Manichaeans as it was inscribed on the inside: "Society of the Religion (or Teaching) of Light".

Fig. 11. Brown glazed bowl used by the Manichaean sect. (Photo S. Lieu, 1990).

Also found were hundreds of fragments of similar bowls with identical inscripions or nearly identical ("the Treasure of the Religion of Light"). There is every possibility that they were once used for the communal eating of vegetarian meals by the sect.

The large complex of Buddhist temples built below the Manichaean shrine and which totally obscured it from site for three decades was finally levelled in 2004 allowing the shrine to have landscaped gardens (Fig. 1) giving it a "theme-park" effect which it had never experienced before (Fig. 6).

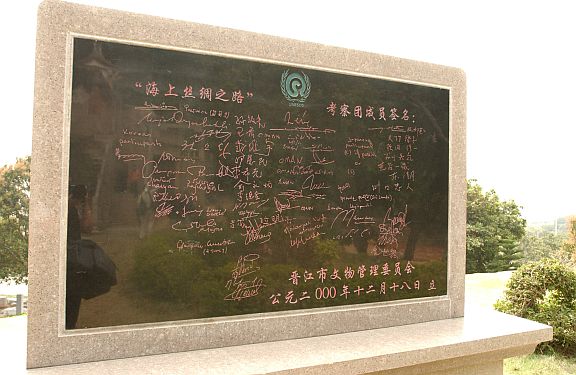

The Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill is now a UNESCO site of historical significance and was visited by inter alia scholars attending the Maritime Silk Road conference in 2000.

Fig. 12. UNESCO plaque carrying signatures of the 2000 conference. (Photo M. Wilson 2004)

The fortunate visitor could even purchase a delicately made porcelain replica of the famous statue (Fig. 13 below). What intrigued the Australian team though was the existence of a second souvenir with Mani the Buddha of Light depicted with more sinicized features including a red visage - a sign of deity in Chinese popular religions.

In 2005, the Australian team made contact with staff of the newly opened Jinjiang Municipal Museum where they were introduced to Mr Nien Liangto - a scholar who has done a great deal of field research on folk religions in the vicinity of the Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill. He had shown the team a photograph of a fairly (over a century?) old statue of Mani with a red-painted visage.

Fig. 13. Souvenir statues of Mani sold at the shrine. (Photo S. Lieu, 2005).

The modern cult of Moni (Mani/Muni) the Buddha of Light

With the help of local worshippers at the shrine, the Australian team (including international research partners) in 2005 was able to track down this extraordinary image to the village of Sunni where several thousand local residents are still followers of the cult of Mani the Buddha of Light. However this was not the Manichaeism of old, but a Buddhist revival cult which began in the 1920s but based on the worship of the extraordinarily well preserved statue of Mani in the shrine on Huabiao Hill (see above Fig. 7).

The name Mani in China shares the same characters (moni) as the -muni part of the name of Buddha (Sakyamuni). Hence it would have been extremely easy for the propagator of the new cult - a Buddhist monk with unbounded evangelical zeal - to pronounce that the statue of Mani was none other than that of the Buddha - Sakyamuni. The local worshippers probably still think that it was the latter which was the subject of the international interest and the staute in the shrine must therefore be that of a deity of great efficacy! Even Mr. Nien Liangto admits in a study published in Chinese that international interest in the shrine as a unique relic of Manichaeism has greatly added to the revival of Buddhist folk religions in the disctrict of Jinjiang.

The full story of how the Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill became a Buddhist temple of major local significance is explained in a lengthy temple-inscription in Chinese on the wall of the shrine which awaits translation into English by the Australian team.

Fig. 14. A sinicized image of Mani the Buddha of Light still venerated in the village of Sunni. (Photo S. Lieu, 2005)

Fig. 15. A UNESCO-cargo cult? Professor Nicholas Sims-Williams FBA inspecting the statue

of Mani the Buddha of Light in a local shrine at the village of Sunni. (Photo S. Lieu, 2005).

Nestorian Christian Remains in Quanzhou (part 1)

Nestorianism (or more correctly the Church of East) reached China in the 7th Century CE from the Sassanian Persian Empire via the Silk Road. The migration was intensified as a result of the conquest of the Sassanians by the Arabs in the following century. The religion was given permission by imperial court for diffusion as early as AD 638 and was first called "the Persian Religion (or Doctrine)" (Bosijiao) because of its long connection with Sassanian Persia. However the leaders of the sect (who were mainly Syriac-speakers) petitioned hard for the religion to be renamed the "Roman Religion" (Da Qinjiao) which was duly granted (AD 745) and this unique term is found on inscriptions in Chinese in Quanzhou which is a surprising example of continuation as Nestorianism is much better known in Medieval China as "the Luminous Religion" (Jingjiao).

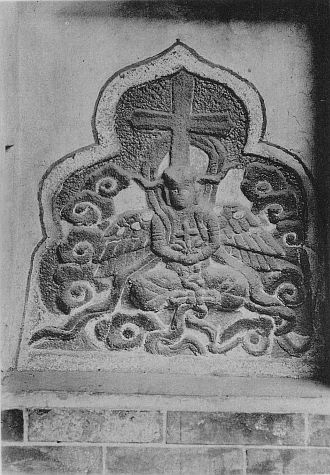

Evidence of a Nestorian presence in Quanzhou first came to light in the 17th Century when Catholic missionaries noticed what appear to be grave stones decorated with the typically Nestorian 'Cross-on-the-Lotus' symbol embedded either in its medieval walls or used as rockery in gardens.

Fig. 16. Headstone with Cross-on-Lotus symbol. (B2, Photo Wu Wenliang c. 1940)

A much more significant find was a headstone with an angel-figure with four wings holding a Cross-on-the-Lotus symbol. The best photograph of this stone was taken by the art historian Gustave Ecke c. 1927 which he found preserved in a local Daoist temple in Quanzhou.

Fig. 17. Headstone with Christian angel with four wings. (B4, Photo Ecke, op. cit.)

The Christian material almost all date to the Yuan Dynasty (c. 1260-1368), i.e. the period when China was ruled by the Mongols, during which Quanzhou became a sea-port of major international significance. The fact that some of the inscriptions are in Phags-pa - a Mongol script developed in China in the course of the Yuan Dyansty puts the dating beyond all doubt.

The building of a railway in the 20th century and the decision to further demolish the walls to prevent its use by the Imperial Japanese Army in 1938 led to further discoveries, mainly inscribed or decorated headstones which once formed parts of Christian sarcophagi. Many of the finds were rescued by the local school teacher and antiquarian by the name of Wu Wenliang who was also responsible for locating the Manichaean shrine on Huabiao Hill.

Wu kept most of the finds in his backyard and began systematically to catalogue the finds (which included Christian Islamic and Hindu material). This he published in a seminal work (Quanzhou zongjiao shike (Religious Stone Inscriptions at Quanzhou), Beijing 1957) while holding a fellowship at the Academy of Sciences in Beijing. His collection and his energy and enthusiasm eventually led to the formation of the now famous UNESCO-sponsored Quanzhou Museum of the History of Maritime Contacts by the East Lake.

Fig. 18. The Quanzhou Maritime Museum. (Photo M. Wilson, 2004)

Sadly Wu did not live to witness this major event as he was a victim of the Cultural Revolution (d. 1969). The artefacts collected by his father, mainly tombstones, now constitute the main collection of the Epigraphical Gallery of the Quanzhou Museum of the History of Maritime Contacts (Quanzhou Maritime Museum for short). His son Wu Yuxiong continued his work and was able to publish a major second edition of his father's monograph-catalogue in 2005. The numbering of the artefacts in this catalogue (usually a letter B followed by a number) has been adopted for this web site to avoid any duplication althought the Australian team has hitherto used its own system with a letter Z (for Zayton) followed by a number in its publications.

Nestorian Christian Remains in Quanzhou (part 2)

That most of the Christian funerary material collected by Wu date to the Yuan Dynasty (c. 1260-1368) when China was under Mongol rule is beyond doubt as some of them cary inscriptions in Phags-pa - a Mongol script which was developed in China. The Christian community in Quanzhou were mainly immigrants from Central Asia who were employed by the Mongol Khans as civil servants to administer the important port city of Quanzhou - a major source of revenue for the imperial coffers.

Fig. 19. Tombstone of Madame Qizi in Phags-pa and Chinese. (B44, photo M. Wilson 2004 )

A significant number of Nestorian Christian inscriptions are in the Syriac script but the language is a mixture of Syriac and Old Turkish (Syro-Turkic for short). This mixing of a Semitic and an Altaic language has greatly increased the problem for the researcher.

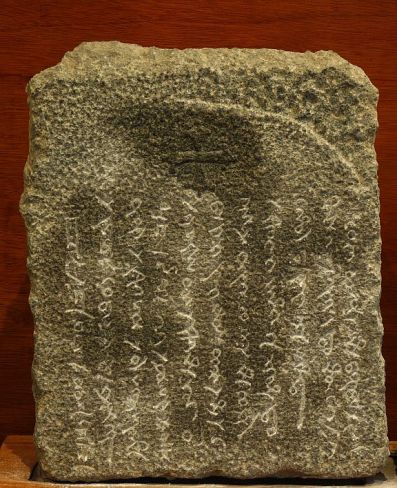

Fig. 20. Tombstone of the Christian Tasqan in Syro-Turkic. (B17, photo M. Wilson, 2004)

One text however which has been successfully deciphered by Professor Niu Ruji in Xinjiang University (Urumqi) is inscribed in a very clear script (B17 = Fig. 20 above). The style of the script and some of the language is similar to a bilingual Chinese and Syro-Turkic inscription found in Yangzhou - also an important city with a foreign community and one which Marco Polo claimed to have administered on behalf of Kubilai Khan.

Like most Nestorian inscriptions in Syriac and in Turkish from Central Asia, a dual system of calendar was employed, the Seleucid (inaugurated in BC 311 by Seleucus, one of the successors of Alexander, hence referred to as "by the reckoning (or computation) of Alexander") and that of the Turco-Chinese (using the 12 animal cycle). An earlier attempt by two British scholars of Syriac (Segal and Goodman) to decipher this text were sadly ignorant of this practice and thought that the name of the deceased was Alexander nor were they aware of the fact that the language was a mixture of Syriac and Turkish.

For Nestorian funerary texts in Syro-Turkic from Central Asia see the preliminary study by the Rev. Dr Wassilios Klein at:

http://www.bethmardutho.org/index.php/hugoye-author-index/142.html

Niu's translation of the text reads ('Nestorian Grave Inscriptions from Quan¬¬zhou (Zaitun) China', Journal of The Canadian Society for Syriac Studies, 6, 2005, 57):

"In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. In the year one thousand six hundred and ten according to the computation of Emperor Alexander and in the year ten of the Ox according to the Chinese computation, on the twenty-sixth of the tenth month, the priest Tasqan, son of Tuhmis Ata Ar, native of the city of Chotcho, a the age of sixty-seven years, went to this city of Zayton and fulfilled the will of God (i.e. died). May his soul be in Paradise. Amen."

Nestorian Christian Remains in Quanzhou (part 3)

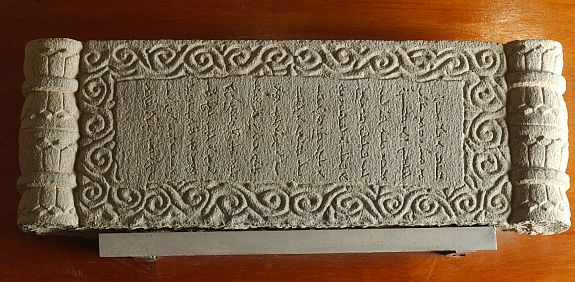

Fig. 21. Funerary inscription in Syro-Turkic (AD 1305). (B20, Photo M. Wilson, 2004)

An inscription with 15 lines in Syro-Turkic which drew the attention of the Australian team is a sarcophagus panel inscribed in a fairly clear hand (B20 = Fig. 21). Most of the more elaborate funerary monuments consisted of two or more panels. The fact that the first lines contain a Trinitarian formula means we are dealing with the text at its very beginning. However, the last few lines are poorly preserved and it was not until 2005 that the team was informed by one of the technicians that the inscription on exhibition at the Quanzhou Maritime Museum is in fact a well made replica and the original has been sent for safe-keeping in the Museum of History at Beijing. The fact that the replica was clearly made by technicians who are not trained in Syriac orthography greatly complicates the process of decipherment.

Fortunately the original 1957 publication of Wu Wenliang contains a reasonably legible photograph of the inscription as well as a that of a squeeze of the inscribed part of the text. With the help of Professor Dr Peter Zieme, Director of the Turfan Research Institute of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy (Akademien Vorhaben Turfanforschung), the team was able to arrive at the following tentative translation:

"In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, forever, Amen. In the year one thosand six hundred and sixteen of the reckoning of Alexander the the Great King (lit. king having a realm), son of King Philip from the city of Macedonia (= AD 1305), in the Year of the Dragon of the Chinese reckoning, on the 12th night of the ninth month in the ecclesiastical calendar, let ... be remembered ..."

Vital to this version is the reading by Professor Zieme of the word sürüg in line 13 - a Turkish word which means a "herd" and is used by Nestorian Christians for "assembly" or "congregation". The reading is reinforced by the fact that the word is followed by the word for "reckoning" or "computation" (saq(ï)ïsï) and what appears to be more numbers written in words and not ciphers. Macedonia was of course a state and not a city. The seemingly awkward phrase "from the city of Macedonia" is an attempt to translate the word "Macedonian" in Syriac.

Working under the same handicaps as the Australian team, Niu (ibid. p. 58) has produced a translation for the same inscription with a number of differences:

"In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, for ever and ever, Amen. According to the computation of the King (and) Sovereign Alexander son of the Sovereign Philip, native of the city of Macedonia, in the year one thosand six hundred and sixteen, and according to the Chinese computation of the Year of the Dragon, the tenth month, the sixteenth (day), this is the grave of George. Amen! ... let there be commemoration."

The Australian team has planned to visit the Beijing Museum of History in 2007 and, hopefully, it will be granted permission to inspect the original stone and solve the problem readings from line 13 onwards!

Some of the texts in Syro-Turkic are over 30 lines long and when deciphered will constitute some of the longest known texts in this hybrid language.

Fig. 22 A funerary panel with Syro-Turkic inscription awaiting decipherment. (B19, photo M. Wilson, 2004)

Though Syriac was the preferred script, Uighur, one of the major representatives of the East languages was also used for inscription by Nestorians.

Fig. 23 Replica of a Christian funerary panel with inscription in Uighur (East Turkic). (B23, photo M. Wilson, 2004)

The inscription which is also a replica (the original was sent for safe keeping to the Museum of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Xiamen and cannot now be located), is interesting in that it does not employ the Seleucid system of calendrical computation nor is it prefaced by a Trinitarian formula. The following translation by the Australian team owes a great deal to the editio princeps of this important text by Dr James Hamilton and Professor Niu Ruji ('Deux inscriptions funéraires turques nestoriennes', Journal Asiatique, 282 (1994) 156):

In the Year of the Sheep, the second day of the man (i.e. full moon) period of the month of fasting (i.e. the twelfth month), (= 31st December, 1331? CE) the Lady (i.e. wife) of the Christian (ärkägün) Quplug Xubilgan, Martha Terim fulfilled the commandment of God (and) ascended to the divine heaven.

Important is the use of the term ärkägün for Christians - a term which may go back to the Greek word for archon. The Chinese version of the term is found in one of the very few Nestorian inscriptions in Chinese in the Marimtime Museum. Found in 1984, its use of literary Chinese as the medium for epigraphy shows that the Nestorian community in Quanzhou was clearly aware of the fact that they were living in a society in which Chinese language and culture were predominant. Its similarity to the panel with Syro-Turkic inscription shows that it too was a sarcophagus panel and the monument itself might have contained inscribed panels in both Syro-Turkic and Chinese.

Fig. 24 A Christian funerary panel with inscription in Chinese. (B51, photo M. Wilson, 2004)

In translation the text reads:

" ... when I stand at the Gate of Light, under (divine) blessing, even if not an incarnation of the Buddha (i.e. God) at least a disciple of the Buddha. With no regrets over life or death, I will ascend direct to Paradise. In the third month of the Tenth Year of Dade (AD 1306). Set up by the Prior of the Mar (Wu) Antonius (Andonisi) of the Xing Ming Monastery of the Christians (Yelikowen) of the various districts of Quanzhou."

Nestorian Christian Remains in Quanzhou (part 4)

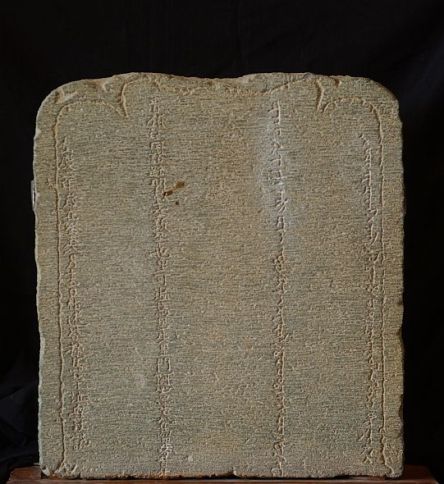

The term Yelikowen is found again in one of two bilingual Syro-Turkic and Chinese inscriptions in the Museum and the text is unique as it concerns both Nestorians and Manichaeans in South China:

Fig. 25 Replica of bilingual epitaph of Bishop Mar Solomon. (B37, photo M. Wilson 2004 )

This too is a replica and the original has also been deposited for safe-keeping at the Museum of History at Beijing. The Syro-Turkic section reads as follows:

This is the tomb of the the Most Reverend Bishop Mar Solomon of the Circuits (lit. realms) of Manzi (i.e. South China). Zauma (= Syr. Sauma), the administrator-in.chief, wrote this on the fifteenth day of the eighth month of the Ox year.

The reading of the place name Manzi (foreign name for South China under the Song and Yuan) is the result of team research and is supported by the Chinese version which reads in translation:

"To the Administrator of the Manichaeans (Mingjiao) and Nestorians (Qinjiao) etc. in the combined Circuits of Jiangnan, the Most Reverend (Mali Haxiya = Syriac mari hashiya) Christian (Yelikewen) Bishop (abisiguba = Syr. episkopa from Gr. episkopos) Mar Solomon (Mali Shilimen), Timothy Sauma (Tiemida Saoma) and others have mournfully and respectfully dedicated this tombstone in the second year of Huangqing, guichou, on the fifteenth day of the eighth month (5th September, 1313)."

Only the Chinese version mentions the fact that Mar Solomon was bishop of both Nestorians and Manichaeans. It is possible that his unique position reflects a deal struck by Marco Polo at the court of Kubilai Khan to accept Manichaeans at nearby Fuzhou under the administration of the Nestorians.

While many of the inscribed tombstones in the Epigraphical Gallery of the Quanzhou Maritime Museum are of a monumental nature and in Syro-Turkic, a number, as noted already (see above Fig. 19), are of a plain design with inscriptions in Phags-pa and Chinese. This simple tombstone (below

Fig. 26) was discovered in 1947 and is a good example of the cultural adaptation undertaken by members of the Christian community in Quanzhou during the Mongol period.

The depiction of an open canopy over a cross on a lotus flower is found on several other tombstones from the city and is unique to Quanzhou. The iconographic motif of the open canopy is taken from Buddhist art where it appears over a Buddha or Bodhisattva. It draws attention to the royalty and divinity of the figure protected by it.

Fig. 26 Image of tombstone with canopy (B39, photo M. Wilson 2004

A canopy or parasol was used in ancient India to protect kings and other royals from the sun, and it subsequently became a symbol of power and prestige. It was natural to use a canopy in association with the Buddha as he had been a prince before attaining enlightenment. It can be seen in the early Buddhist art of India, and was transmitted to Central Asia and China where it appears, for example, at Dunhuang. A similar canopy to the one shown on this tombstone can be seen on a panel relief on the Eastern pagoda of the Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou, completed about 1250.

Fig. 27 Buddha under a canopy on a relief in the Kaiyuan Temple (photo M. Wilson 2004).

The discovery of its presence on Christian tombstones of the Mongol period is quite remarkable, and yet explicable in the context of the multiculturalism of Quanzhou. The canopy has tassels or streamers dangling from it and protects the cross emerging from an open lotus flower.

Nestorian Christian Remains in Quanzhou (part 5)

To the bottom left and right of the tombstone (see above Fig. 26) are unfurled scrolls terminating in lotus flowers and each scroll has a line of Chinese characters. The characters read: "Virtuous (sic) Esquire/Bishop Huang, aged ninety-three". It is clear from the name that the deceased was of Chinese origin, and suggests that not only Turkic-speakers from Central Asia but Chinese from the local population belonged to the Church of the East community at Quanzhou. The tombstone has an outer border design and is pointed at the top, elements common to several other tombstones found in Quanzhou. The tombstone itself was probably used as a grave marker rather than being a part of a sarcophagus.

Fig. 28 Relief of angels with cross on a lotus flower symbol (B31, photo M. Wilson 2004).

This stone panel was unearthed in 1946 and appears to be a section of a sarcophagus. It is one of the best preserved and clearly defined of the relief sculptures so far discovered at Quanzhou. The panel depicts two flying figures holding a stand which supports a cross on a lotus flower. The motif of

two angels holding a garland or rounded enclosing a cross or the monogram of Christ is known in Christian art from the fourth and fifth centuries onwards (see Fig. 28 below).

The use of a stand to support the cross on a lotus flower instead of a roundel enclosing the cross is a significant development. The two figures are dressed in flowing draperies with billowing scarves and trailing ribbons and are reminiscent of Apsaras or flying attendants in Buddhist iconography.Both

figures wear decorated crowns and have long side locks. Notable are their decorated shoulder pieces known as 'cloud shoulders' which were worn by fashionable ladies and dancers at the Mongol court.

Fig. 29 Angels with cross symbol from Late Anqituity (photo Ken Parry, 2005)

A similar 'cloud shoulder' is worn by a figure on a panel relief on the Eastern pagoda of the Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou, completed about 1250 (see below Fig. 30).

Fig. 30 Standing figure with cloud-shoulder (photo M. Wilson 2004).

The exact detailing of the two figures shows that the stone carver responsible for this panel was keen to demonstrate his knowledge of contemporary Mongol costume. A winged angel with Mongol features from the Seljuk period (12th -13th century) now in the Ince Minare Museum at Konya in Turkey shows parallels with the flying figures from Quanzhou (see Fig. 31 below).

Fig. 31 Relief of angel from Konya (Iconium) in Turkey (Seljuk-Mongol period) (photo Ken Parry 2005)

Medieval Catholic Remains in Quanzhou

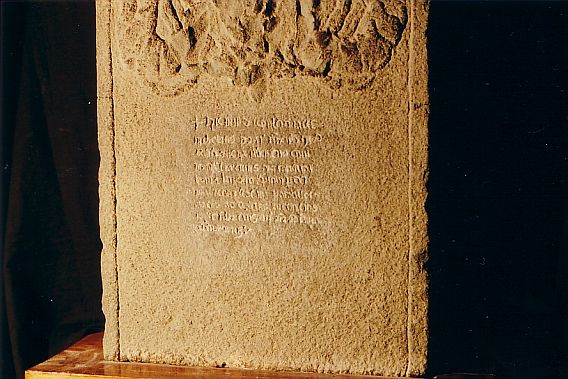

Zayton was the landing place in for a papal mission led by John of Montecorvino and one of his followers, Andrew of Perugia was buried in the city and his epitaph is the sole representative of a brief but well documented Catholic mission to the court of the Mongols.

Fig. 32 Replica of Latin epitaph of Andrew of Perugia. (B15, photo M. Wilson 2004)

The mission which consisted mainly of Franciscan monks arrived in Beijing (then known as Dadu = Chinese for "Big Capital") or Khanbaliq = Turkish for "the Khan's city") c. 1313, probably entered China via Zayton. Its overt mission was to convert Kubilai Khan to Christianity but the latter had died before their arrival. The mission met with very little success in the capital where they were shunned by the Nestorians and some of the Franciscan monks later obtained a concession from the Mongol rulers for the establishment of a small mission in Quanzhou and a succession of three Bishops of Zaitun is known: Gerard, Peregrinus of Castello and Andrew (Andreas) of Perugia. The last named, who died in AD 1332, is commemorated in this the oldest known Latin sepulchral inscription to be found on Chinese soil (see above Fig. 26) and the fact that he was episcopus of Cayton confirms for the first time the link between medieval Zaitun and modern Quanzhou.

Discovered in 1946, a photograph of the stone taken by Wu Wenliang was sent to John Foster - a scholar of Nestorianism in China - in the UK who identified the language as Latin and sought the advice of Professor C. J. Fordyce then Professor of Humanity (i.e. Latin) at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Fordyce's partial decipherment published by Foster in 1954 ('Crosses from the walls of Zaitun', Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (N.S. 1954) 19) remains unsurpassed even though a conference in the honour of Andrea di Perugia had was in September, 1992 in Perugia (cf. C. Santini (ed.) Andrea di Perugia, Atti del Convegno (Perugia, 10 Settembre, 1992), Rome, 1994), no significant improvement had been made to the preliminary version of Fordyce:

¿ Hic (in PFS) sepultus est

Andreas Perusinus (de-

votus ep. Cayton .......

.......ordinis (fratrum

min.) ..................

... (Jesus Christi) Apostolus

............................

........(in mense) .......

M (cccxx)xii +

The only other major medieval Latin inscriptions found in China are all from Yangzhou and provide almost no parallel phrases which may help scholars to decipher the text from Quanzhou as the deceased were all laypersons while Andrea of Perugia was a cleric. Although the original stone is now in safe-keeping in Beijing, the inscription is too badly eroded to allow for easy decipherment.

Publications

For preliminary reports of the project by members of the Australian team see I. Gardner, S. Lieu and K. Parry (eds.) From Palmyra to Zayton, Epigraphy and Iconography = Silk Road Studies X (Turnhout, 2005) pp. 189-278 (with 26 illus.)

The final reports will be published as a volume in the Series Archaeologica of the UNESCO-sponsored series Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum in c. 2009.